Public Water brings attention to the rarely-seen labor that humans (and non-humans) do to care for New York City’s drinking water.

The project takes multiple forms, including a year-long digital campaign, large-scale public sculpture, and education initiatives.

A Year of Public Water

Digital Campaign

June 2020 – June 2021

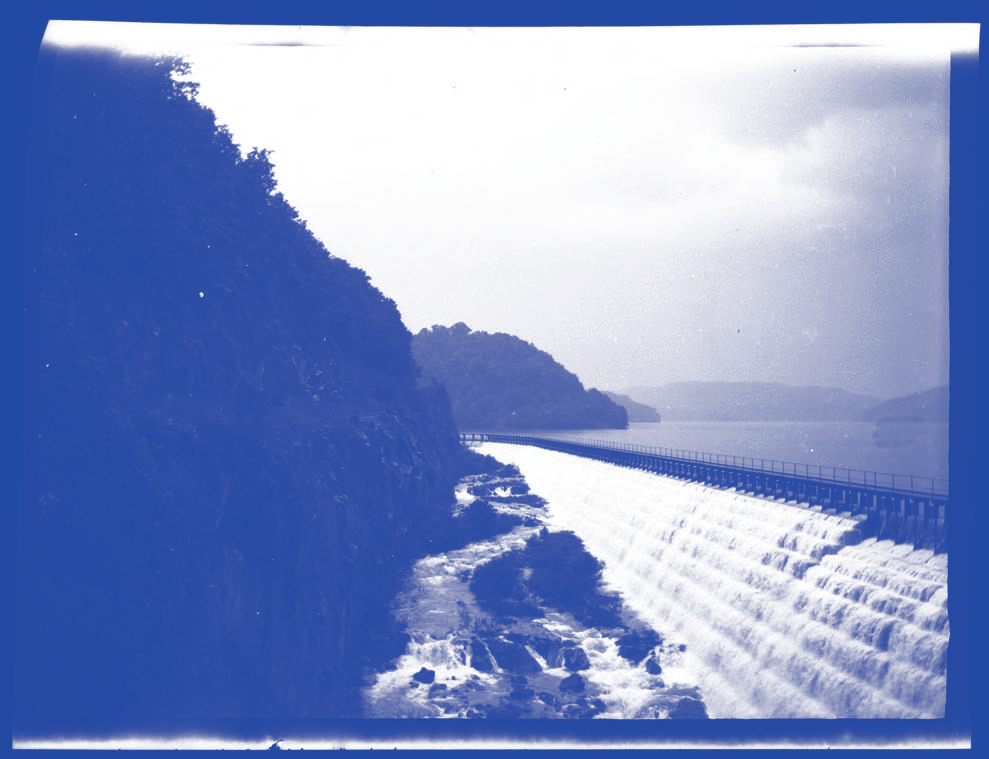

A Year of Public Water is a campaign that highlights the history of New York City’s water supply system and examines ongoing issues of water quality, access, privatization and infrastructure facing the NYC drinking watershed–which provides more than a billion gallons of clean water daily to nine million state residents. The project is organized by artist Mary Mattingly in collaboration with More Art, a non-profit organization that commissions socially engaged public art projects. The campaign took form digitally on this website and in connection with various social media outposts in 2020 and 2021 where new content was released weekly including research, guest interviews, and calls to action. The anchor of the campaign is A Story About the NYC Drinking Watershed, a narrative telling of our city’s water that was shared incrementally throughout the year. The story begins in geologic time and ends where we are today, with constant threats to water and land as the current administration continues to chip away at environmental protections long fought.

The project is an invitation to examine one’s relationship to water in order to co-build more equitable partnerships between urban water consumers and upstream water-producing communities. Building an in-depth understanding of human care, community stewardship, reciprocal relationships and the long standing history of New York City’s watershed and drinking water system, the campaign culminated with the unveiling of a sculpture—a water-filtering, sculptural ecosystem—and public programming at Prospect Park in Spring/Summer 2021.

Watershed Core

Sculpture and Public Programming

Prospect Park, Brooklyn NY

June 3 – September 7, 2021

Public Water was a multisite project and installation by Mary Mattingly that took place June 3 – September 7, 2021 at the Grand Army Plaza entrance to Prospect Park in Brooklyn (Google Map it), presented in partnership with Brooklyn Public Library, Prospect Park Alliance and NYC Parks.

The sculpture, titled Watershed Core, is a 10ft tall geodesic dome designed as a structural ecosystem covered in native plants that filter water in a gravity-fed system that mimics the geologic features of the watershed. “Watershed Core is an active sculpture that follows A Year of Public Water, a timeline recounting the building of New York City’s drinking watershed,” said Mary Mattingly. The sculpture draws from the minerals and geologic features of the watershed to filter water. PUBLIC WATER brings attention to New York City’s drinking water system in order to build more reciprocal exchanges between people who live in New York City’s drinking watershed and its drinking-water users in the city, to promote care and commons.

In conjunction with the sculpture, More Art and Mattingly have produced Waterways and Woodlands, a self-guided walking tour that natural and human-made ecosystems found in Prospect Park, and its connection to New York City’s water supply. The tour addresses filtration, natural systems of water remediation (including the ecoWEIR system being employed in the park), New York City water systems, reservoirs, and the New York City watershed. The audio guide is powered by Gesso and available to stream here.

Public Water is produced by More Art and Mary Mattingly in partnership with the Brooklyn Public Library, Prospect Park Alliance, and the NYC Parks Department. An earlier version of the sculpture originally appeared as “The Parts Never Lead to the Whole” in the exhibition Stars Down to Earth: Mary Mattingly & Dario Robleto (January 13 – March 13, 2020) at the Central Library.

MORE ART is a non-profit organization based in New York that commissions socially engaged public art projects, reaching over 10,000 spectators a year. More Art supports collaborations between artists and communities to create public art projects and educational programs that stimulate creative engagement with critical social and cultural issues. More Art uses public art and digital media to create powerful experiences that aggregate individual and collective perspectives on sensitive topics, such as immigration. All projects are carried out through multi-year collaborations with local organizations.

www.moreart.org

Mary Mattingly is a visual artist focused on questions of ecology and sustainability and the Katowitz Radin Artist-in-Residence at the Brooklyn Public Library for 2020. She founded Swale, an edible landscape on a barge in New York City. Docked at public piers but following waterways common laws, Swale circumnavigates New York’s public land laws, allowing anyone to pick free fresh food. Swale instigated and co-created the “foodway” in Concrete Plant Park, the Bronx in 2017. The “foodway” is the first time New York City Parks is allowing people to publicly forage in over 100 year. www.marymattingly.com

Prospect Park Alliance is the non-profit organization that sustains, restores and advances Prospect Park, Brooklyn’s Backyard. The Alliance provides critical staff and resources that keep the park green and vibrant for the diverse communities that call Brooklyn home. The Alliance cares for the woodlands and natural areas, restores the park’s buildings and landscapes, creates innovative park destinations, and provides free or low-cost volunteer, education and recreation programs. Learn more at prospectpark.org.

For over 50 years, NYC Parks’ Art in the Parks program has brought contemporary public artworks to the city’s parks, making New York City one of the world’s largest open-air galleries. The agency has consistently fostered the creation and installation of temporary public art in parks throughout the five boroughs. Since 1967, NYC Parks has collaborated with arts organizations and artists to produce over 2,000 public artworks by 1,300 notable and emerging artists in over 200 parks. For more information about the program visit www.nyc.gov/parks/art.

Brooklyn Public Library is among the borough’s most democratic civic institutions, serving patrons in every neighborhood and from every walk of life. Established in 1896, BPL is one of the nation’s largest public library systems and currently has nearly 700,000 active cardholders. With a branch library within a half-mile of the majority of Brooklyn’s 2.6 million residents, BPL is a recognized leader in cultural offerings, literacy, out-of-school-time services, workforce development programs, and digital literacy. In a borough of wide economic disparity, where the costs of basic necessities often take priority over spending on cultural enrichment opportunities, BPL provides a democratic space where patrons of all economic standings can avail themselves and their children of cultural and educational programs in a broad range of disciplines. www.bklynlib.org.

Public Water is supported in part by the Lambent Foundation, the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, the Joseph Robert Foundation, and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. Additional support for educational programming has been provided by the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation. The walking tour and wayfaring installation at Prospect Park is a project of the Environmental Protection Fund Grant Program for Park Services, administered by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation.

Organized by

Micaela Martegani

Shona Masarin-Hurst

Elana Engelman-Lado

Alexandra Hodkowski

Jeff Kasper

Elæ (Lynne DeSilva-Johnson)

Candystore

Samantha Giarratani

Brandi Mathis

Chloe Kellner

Sara Florez Brinez

Tyler Glenn

Art Direction and Design

Shona Masarin-Hurst

Special Thanks

Cora Fisher, Paquita Campoverde, and the Brooklyn Public Library; Deborah Kirschner, Maria Carrasco, Christian Zimmerman (RLA, FASLA), and the Prospect Park Alliance; Elizabeth Masella and NYC Parks; Patrick Callahan and the AP Environmental Science Class at the Bronx Center for Science and Mathematics; Tim Koch and the Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program; Lori Quillen, Jamie Deppen, and the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies; Donna Steffens and the Time and the Valleys Museum; Emily Vail and the Hudson River Watershed Alliance; Melissa Rachleff Burtt, Zack Nacheman, Abby Chin-Martin, Elena Li, Erin Cao, Tessa Kennamer, Kirsten Sunderland and the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at NYU; Christy Gast; Jason Chan; Michael Vitaly Sazanov; Susan Hito Shapiro, Tatianna Cassatt, Alder Phillips, and Samantha Fellers.