From Westchester to a Manhattan Potter’s Field

Many New York City residents viewed the watershed as an abstraction, and yet lived with some of its prominent infrastructure that transformed the face of the city. This included the High Bridge (which carried the old Croton Aqueduct over the Harlem River into Manhattan), Central Park’s two reservoirs, and the Croton Reservoir at Manhattan’s Murray Hill. The Croton Reservoir, with its 50’ high granite walls and public promenade atop, stood where the main branch of the New York Public Library and Bryant Park are today. Before it was a reservoir, the land where Bryant Park now stands was a potter’s field. To build the reservoir, thousands of bodies needed to be exhumed and reburied on Wards Island. The reservoir contributed to 5th Avenue becoming one of Manhattan’s most fashionable streets.

“In the heart of Midtown the New York Public Library’s main branch is one of the city’s most recognizable landmarks. Prior to its construction in 1900 the Murray Hill Distributing Reservoir [also known as the Croton Distributing Reservoir] stood on the site of the library. …Between 1842 and 1900, the four-acre reservoir held 20 million gallons of water for the growing island metropolis. Its previous sources at Collect Pond and various springs across town were running dry and becoming polluted from urbanization. Water contained at Murray Hill originated from Croton Reservoir in Westchester County.”

—Sergey Kadinsky, Hidden Waters blog

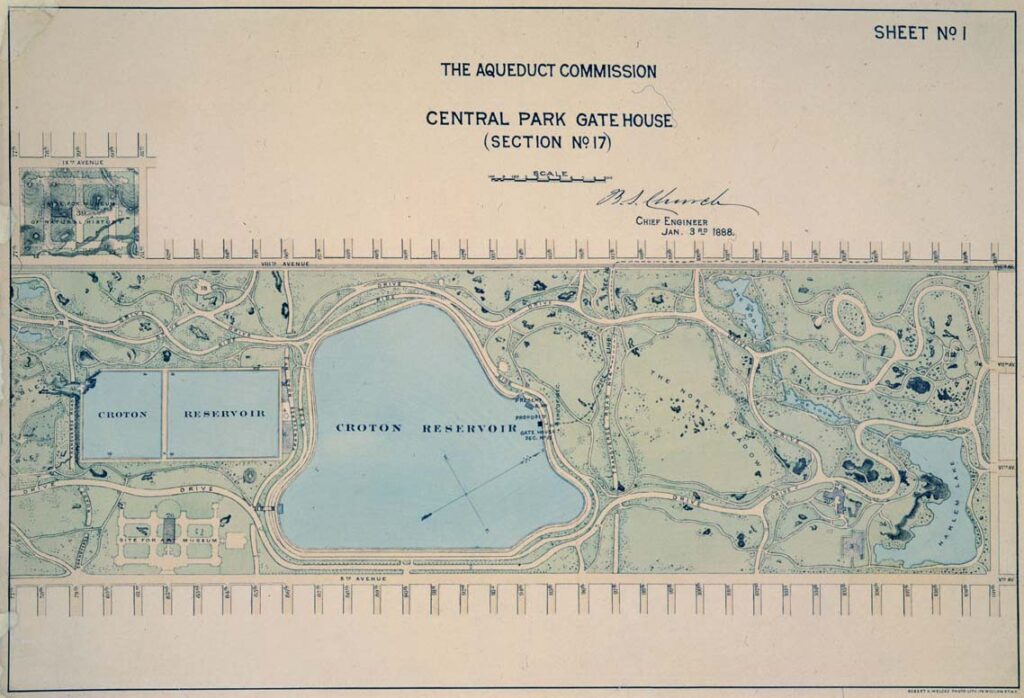

“The rectangular reservoir on the left was part of the original Croton system and first received water from the (Old) Croton Aqueduct on June 27, 1842. Known as the York Hill Receiving Reservoir, it was constructed before Central Park existed and had a capacity of 150 million gallons. The New Receiving Reservoir on the right was constructed between 1857–1862 and though originally a rectangular design was reshaped anticipating the naturalized design of Vaux and Olmstead’s Greensward Plan for Central Park.”

—From “Croton Aqueduct Celebrates 175th Anniversary” by NYC Water.

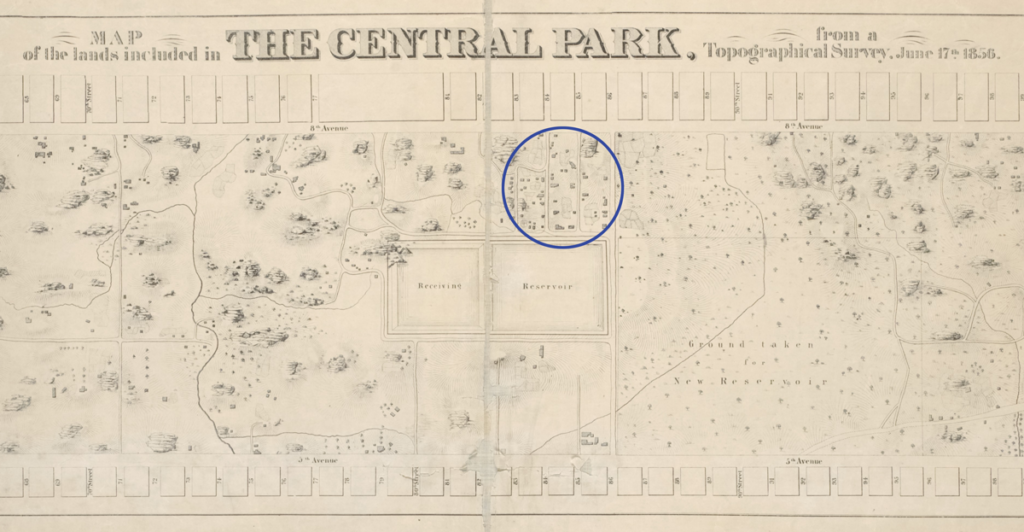

Seneca Village

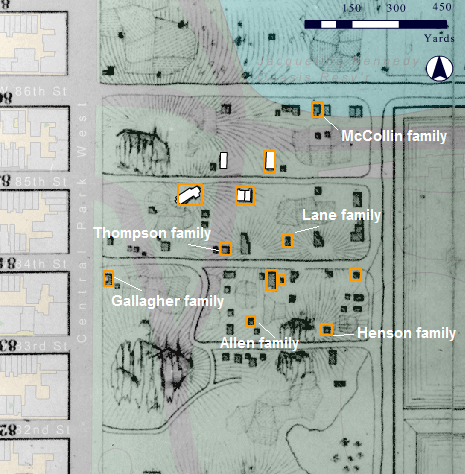

Seneca Village, circled on the map above, was a community displaced by construction of the public water system and Central Park, impacting land and home ownership for Black New Yorkers.

“Prior to the construction of the reservoir, this site was known as York Hill, home to a small African American community that was pushed out in 1838 to make way for the reservoir. Most of the residents relocated a block west to an existing community known as Seneca Village…located between 7th and 8th Avenues…from 83rd to 86th Streets.”

“When the receiving reservoir was built on the village’s eastern border, local residents worked on its construction…”

“The demise of Seneca Village began in 1853, when state lawmakers authorized the creation of Central Park. The Press regarded Seneca Village as a shantytown, but property owners held off condemnation in a protracted two-year court battle. In 1856, the nearly 300 residents were sent eviction notices. The New York Times did not hide the motives behind the inclusion of Seneca Village’s land within Central Park: “The sole object of the authorities in making the Park is to procure their expulsion from the homes which they occupy.”

—Sergey Kadinsky, Hidden Waters of New York City, p. 38.

Further Reading

Murray Hill Distributing Reservoir, Hidden Waters Blog.

Croton Aqueduct Celebrates 175th Anniversary, NYC Water on Medium, 2017.

Seneca Village, National Park Service website.

Seneca Village, Mapping the African American Past (MAAP).

The Bottom: The Emergence and Erasure of Black American Urban Landscapes, Ujijji Davis in the Avery Review.