Water Expansion by Eminent Domain,

Part I

While New York City’s use of eminent domain began in 1830, the New York State Public Health law of 1905 allowed New York City to acquire land through eminent domain specifically for the expansion of the water supply area. The use of eminent domain forced thousands to move involuntarily, creating significant animosity towards the city. The uprooting of these families also affected the economy of the region. Much of the area was dedicated to farming, particularly in low lying land by rivers and creeks, which had more productive soil. However, this was exactly the land that the city took in order to build the reservoirs.

The Relocation of Katonah,

1896 – ca. 1910

“New York City began to develop plans to build the New Croton Dam and enlarge the Croton Reservoir in the 1880s. Katonah was in the path of those plans and eventually its properties were condemned, the owners compensated and the buildings or “improvements” auctioned off. Rather than permanently abandon their village, Katonah residents bought back many of their buildings and moved them to higher ground.”

—Westchester County virtual archives, documents pertaining to the relocation of Katonah.

On Eminent Domain in the Catskills

“[In] 1906 … the legislature passed an amendment requiring New York City to pay one-half of the assessed value of the land before taking possession. In addition to the short period of notice, valuations of land were quite low and led to some property owners and their families being ousted from their homes for as little as $250.” – Page 599

“Section 42 of Chapter 724 of the Acts of 1905 provided for the compensation of consequential damages inflicted on land adversely affected by adjacent condemnation. Yet, when average citizens presented evidence of consequential or indirect damage, the New York City Corporation Counsel objected that the commission did not have jurisdiction to pass on such matters. Furthermore, New York City had the temerity to maintain that since the dam had not yet been built and the reservoir had not been filled, no decrease in the value of businesses or lands had occurred…”

“Corruption and bureaucratic inefficiencies enraged local property owners and fed the negative perception of the City. Speculation was rampant during these years. Landowners also resented the fact that for every dollar that was paid in compensation, the commissions spent more than fifty-four cents on administrative expenses. Commissioners were paid $50 a day plus expenses and appraisal witnesses paid between $10 and $50 per day. To see the perpetrators of their injustice enriched while many were reduced to poverty, created deep and lasting bitterness toward the City. It is unsurprising, therefore, that bitterness and hostility were pervasive. The infirmity of the 1905 laws coupled with the actions of the City and the commissions created and perpetuated these feelings.” P 604-605

—“New York City’s Watershed Agreement: A Lesson in Sharing Responsibility,” by Michael C. Finnegan in Pace Environmental Law Review, Vol. 14, Issue 2, Summer 1997.

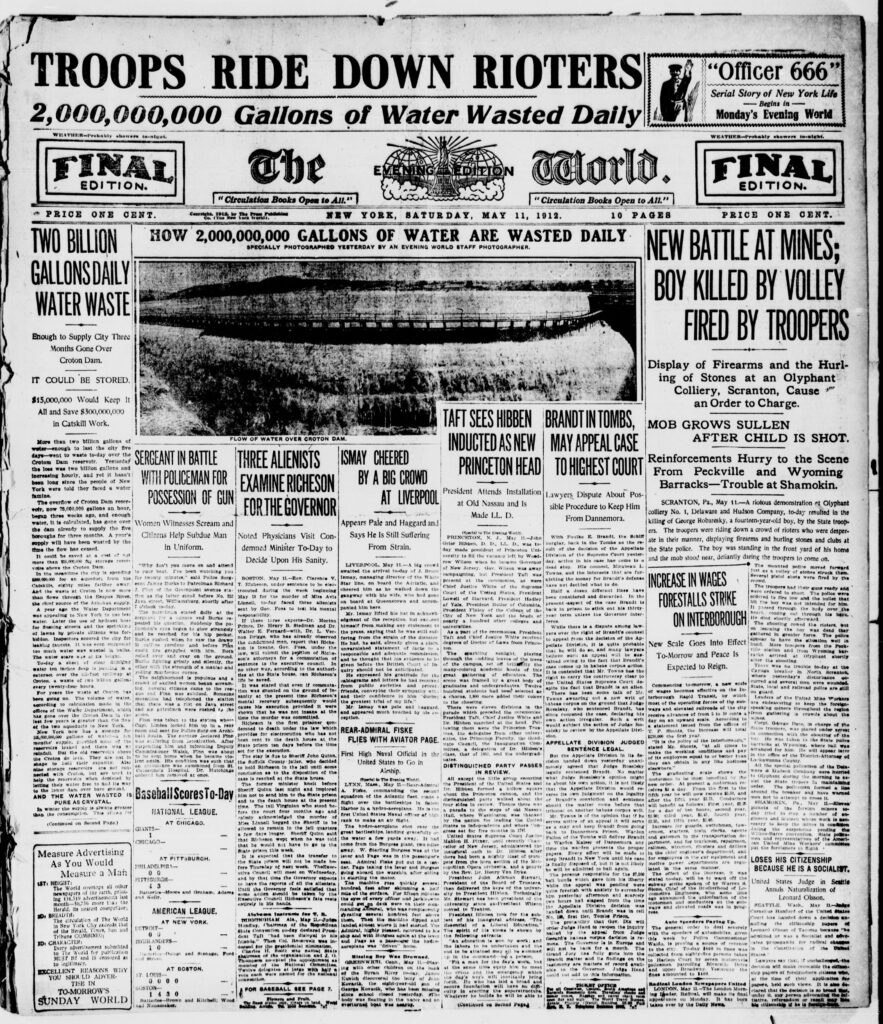

Left, an article on water waste at the Croton Dam in 1912. Leakage at the dam and over consumption in the city prompted questions regarding the need to expand to the Catskills.

“More than two billion gallons of water—enough to last the city five days—went to waste today over the Croton Dam reservoir. Yesterday the loss was two billion gallons and increasing hourly, and yet it hasn’t been long since the people of New York were told they faced a water famine…A year’s supply will have been wasted by the time the flow has ceased. It could be saved at a cost of not more than $15,000,000 for storage reservoirs above the Croton Dam.

In the meantime the city is spending $300,000,000 for an aqueduct from the Catskills, eighty miles farther away. And the waste at Croton is now more than flows through the Esopus River, the chief source of the Ashokan supply.”