Flooding the Catskills

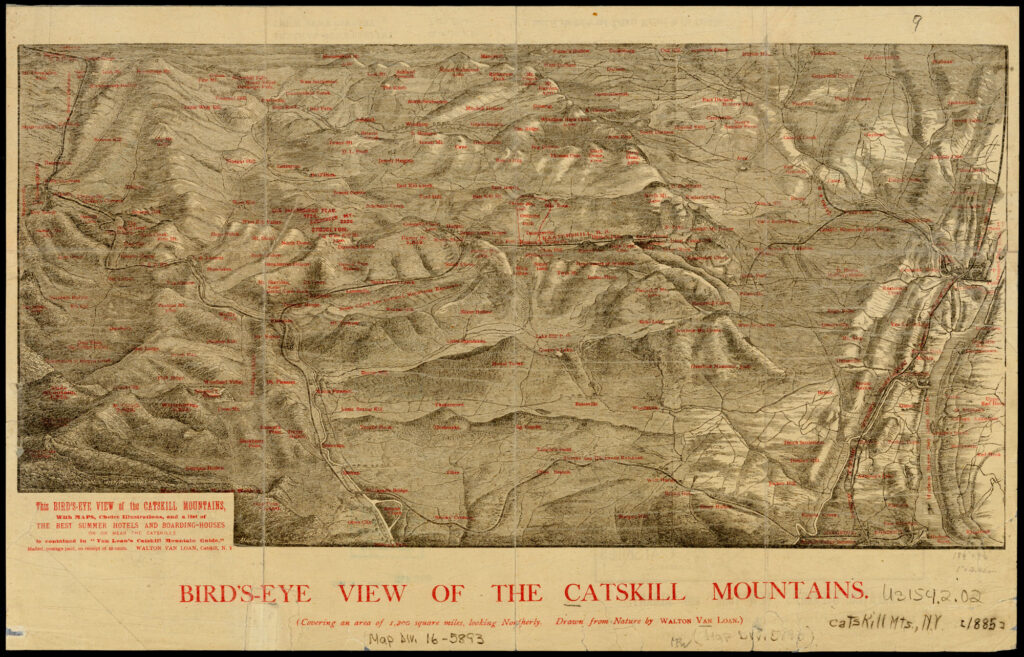

With the sanction of higher political authorities, the city appropriated what it saw as the countryside’s resources, and remade ecosystems to sustain its own growth for decades. While Catskills settlers whose land was taken over by eminent domain did see their day in court, many said they only received a modicum of social and economic justice. While thousands of people obtained steady employment as laborers on the Catskill project, waterworks construction harmed the local economy overall by damaging boardinghouse tourism and flooding fertile agricultural land. History repeated itself, in this case often less violently, and glossed over the sacrifices made by displaced watershed residents.

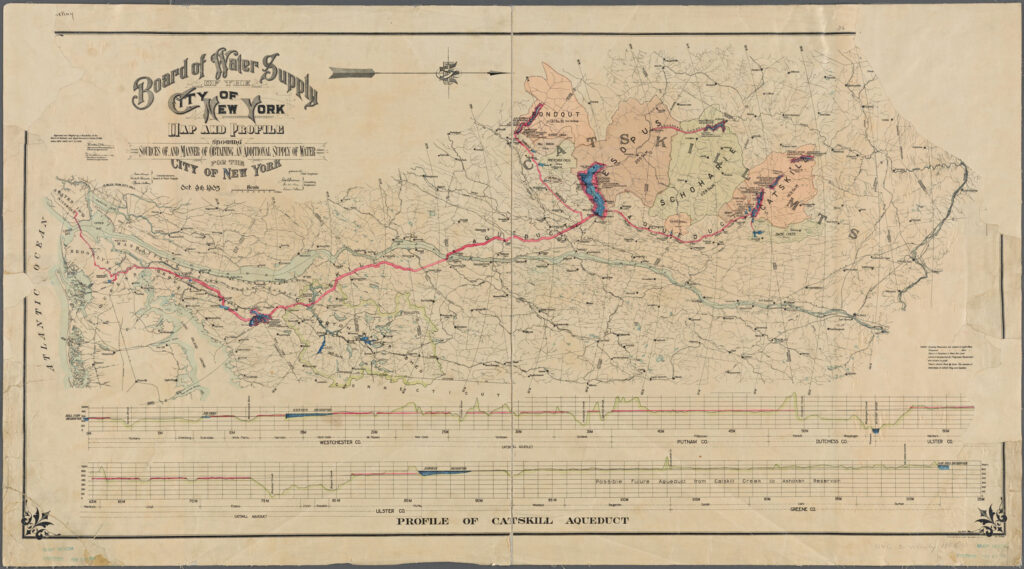

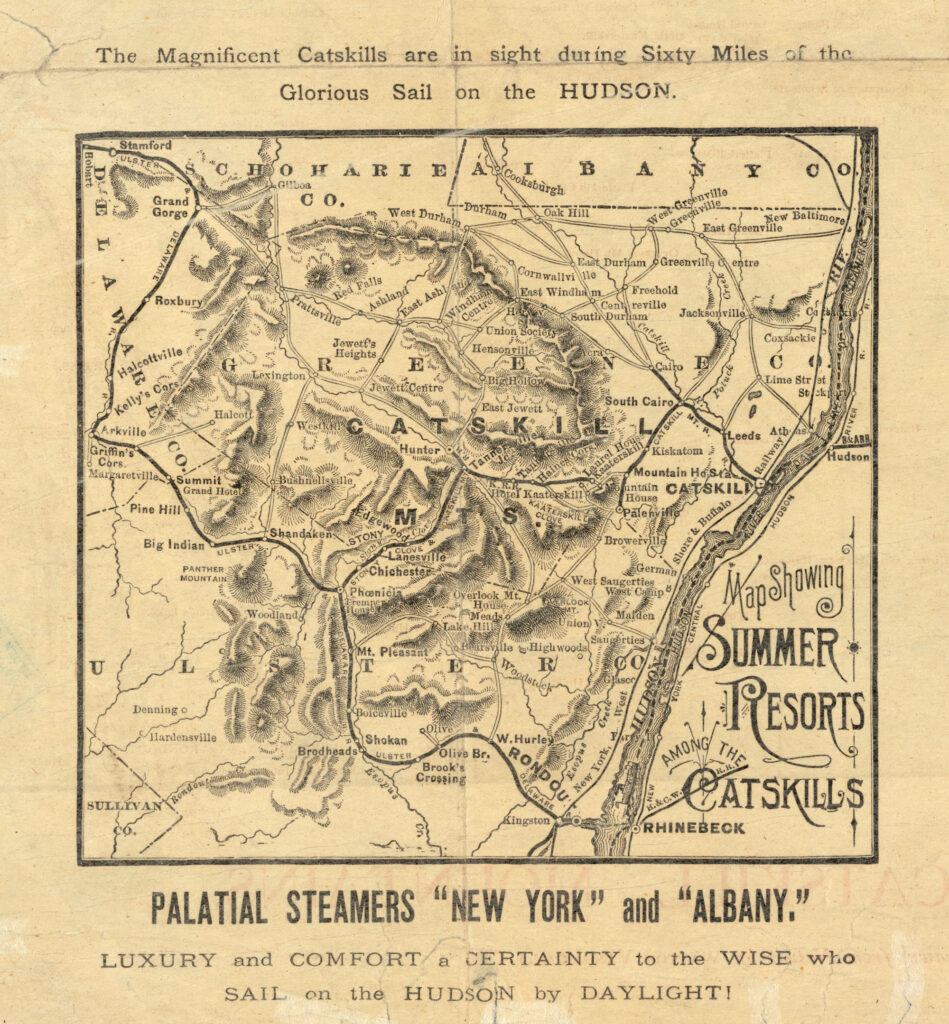

By August 1905 the Board of Water Supply ordered engineers to draw up maps and develop a plan to collect and transport Catskill water. Quickly, they identified Esopus Creek for development of a massive reservoir and retaining dam, which became the centerpiece of the Catskill branch of the NYC water supply.

The City submitted its plans to the State Water Supply Commission, which began a series of public hearings in the Catskill region. Many locals voiced opposition to the City’s plans to seize their land and transform the landscape and their livelihoods with it.

“Objections in the mountains were immediate. A jurist with the serendipitous—and real—name of Judge Alphonso Clearwater, representing the interests of the soon-to-be-affected towns along the creek, declared at a packed public hearing, ‘The powers asked by New York are too great. They ask the power that the Almighty would not delegate an archangel, let alone, if I may use such an irreverent comparison, a Tammany contractor.’”

“Except, who could fight City Hall? Even in the face of lawsuits and complaints, the necessary state authorizations were effortlessly secured, and the city moved quickly. Test borings commenced in early August 1905, nine months before either the city or the state had formally authorized plans to develop the Catskills watershed. Once the appropriate regulations were passed, surveyors moved into the Esopus Valley without warning. Trespassing onto people’s property, cutting down trees, knocking down stone fences–even though no money to purchase lands had been exchanged. Signs also spontaneously sprang up, advising landowners that within two months title to their property would be vested in the city and they would be subject to a ten-day notice to vacate.”

—From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver, p. 184-185.

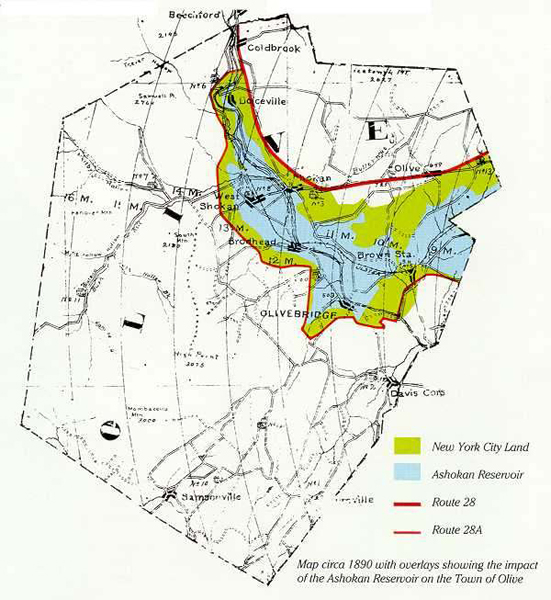

Despite legal challenges, City Hall’s influence held. When the dust settled, 8 villages ceased to exist, 2,000+ residents had been forced to relocate, 500+ homes and 10 schools were destroyed. For those who lost land, this project of urban expansion was devastating, upending a way of life that could not be recovered.

“I began dredging up the story of the forgotten Town of Olive. That story became linked to New York City’s historic quest for clean and abundant water. As I learned of the expansion of the New York City population, I began to envision the movement and confinement, use and abuse of the same water supply system on which millions of New Yorker’s lives depend; that history sheds light on the current efforts to protect the watershed which supplies New York City with drinking water.”

— Camila Calhoun, “A Town Called Olive“

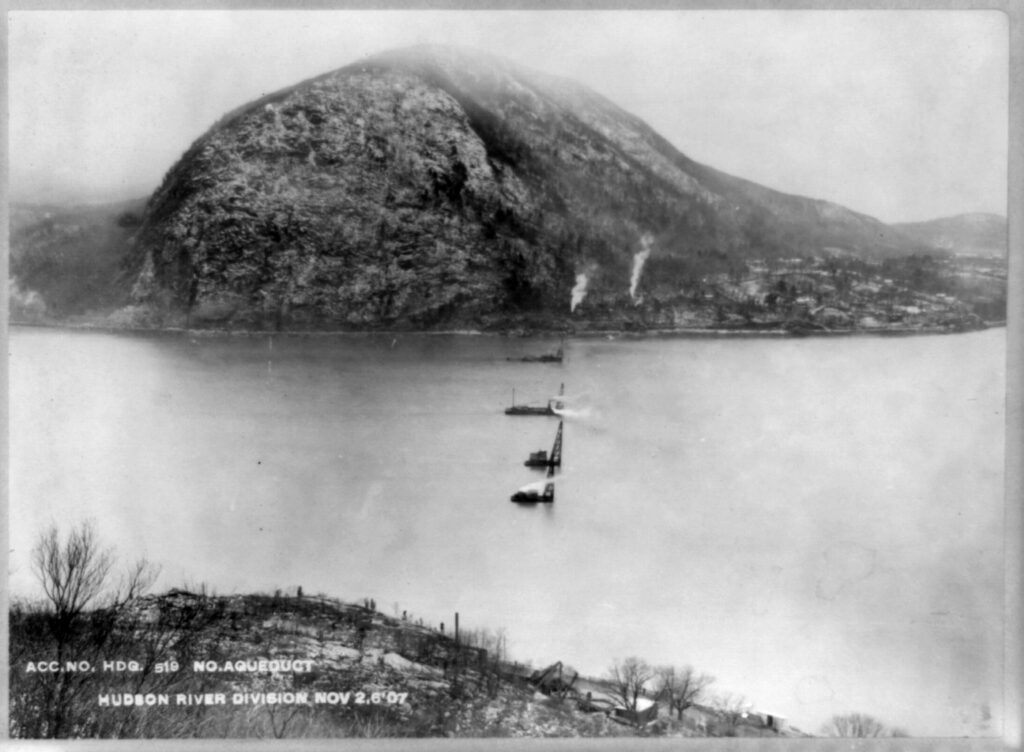

Construction of a new aqueduct began in 1907. Water, pulled by gravity, had to travel from the west of hudson mountains to the southeast, crossing beneath the Hudson River along the way.

“Also gone were the boarding houses and the summer trade. Once the dam and reservoir were finished, “a place and a way of life that had long been supported by old and tested patterns was forever lost,” Steuding further explained. “Within the space of one, or at the most, two generations, the Catskills’ vibrant traditional culture disappeared; the old folks and their old ways were quickly forgotten and, not unlike a fond and fading memory, they soon became the stuff of myth and folklore.” So did villages like West Hurley, Brown Station, Olivebridge, Stoney Creek, and Ashton.”

—From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver, p. 194.

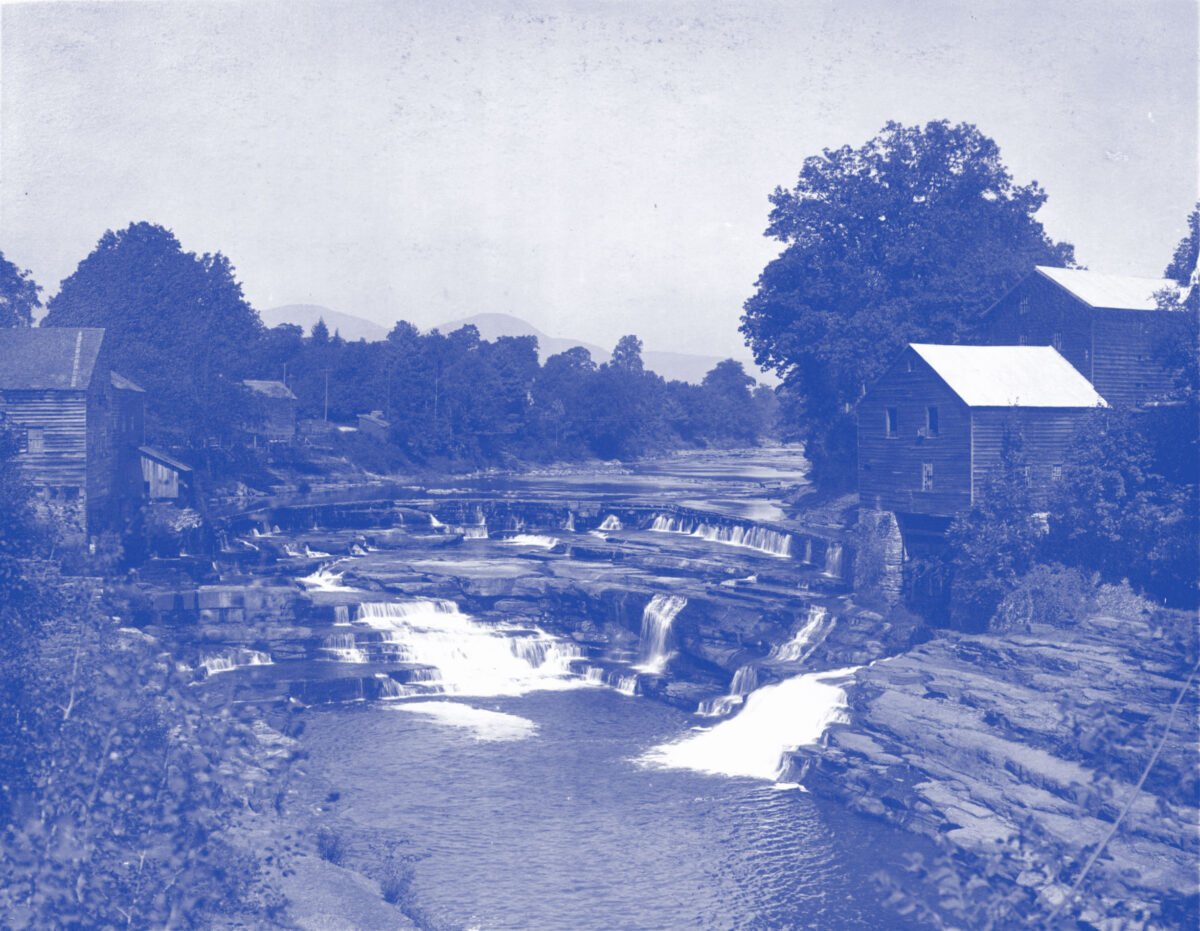

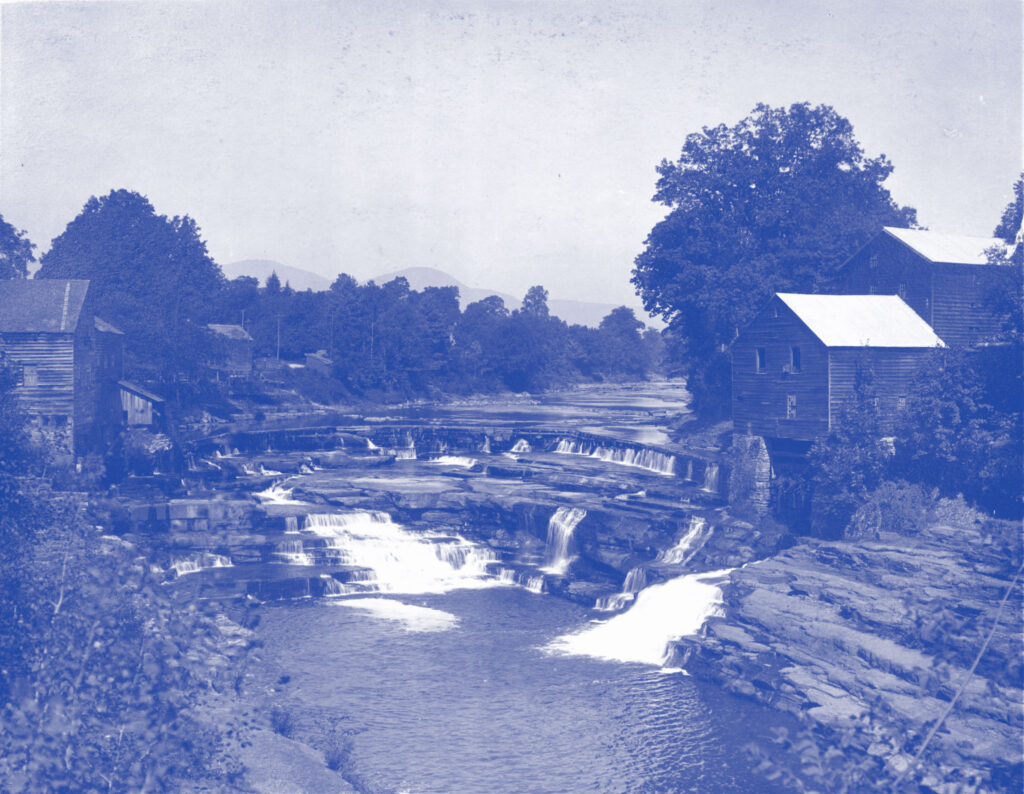

“One target for extinction was Bishops Falls, which would eventually find itself under 190 feet of reservoir water. ‘At the lovely small falls,’ said [ environmental professor David] Stradling, ‘the Bishop family—hence the name, Bishops Falls—built not just a farmhouse, but a sawmill and a grist mill, which were on either side of the falls. They also built a boardinghouse, the Bishops Falls House. From the name alone you could see that this was a family that had lived there for generations, and expected to continue living there for generations. When New York City took their land through eminent domain, several different Bishop families went through the process of divining the right value for their property. As they did this, it became apparent that it was impossible for New York City to pay what was really the value of this place to that family. The Bishop family would not find another Bishop Falls.’”

—From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Sephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver, p. 185-186.

“The transformation of what was once a tranquil rural valley became a noisy, unsightly, gigantic manufacturing zone…” said a Westchester Land Trust account.

—From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America, p. 191.