Privatization, Part II: Hamilton, Burr, and the Manhattan Company

Manhattan’s drinking water went through several privatization schemes as early as the 18th century. These were led by two State Assemblymen, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Burr convinced city officials that public funds would be inadequate to develop a suitable reservoir and aqueduct. He created the Manhattan Company (later to become Chase Bank) to serve the public as the sole supplier of water and took control of the city’s water system in 1799. However, hidden in the bill that granted a charter to the Manhattan Company was a clause that stated that the company could use any surplus capital for other purposes. The company was expected to tap into the Bronx River but instead drilled wells into the polluted Collect Pond, which was much cheaper. Additionally, the company only laid 23 miles of pipes and charged an expensive rate of 20 dollars a year, which made it inaccessible to many citizens. Two thirds of the population still relied on polluted wells or buying spring water from expensive private vendors. Because of these failures, in 1816 several Common Council committees were appointed to investigate whether the legislature could grant the city the right to build a public water supply; however, nothing immediate was done about the toxic water and poor service. The first changes began around 1828 after repeated fires destroyed blocks because water mains and fire hydrants had not been extended to all parts of the city.

Source: NYC DEP Press Release, ‘Department of Environmental Protection Donates 19th Century Wooden Water Mains to New-York Historical Society.’

“On March 30, 1799, state lawmakers passed “An Act for supplying the City of New York with pure and wholesome water.” The law conferred a charter on the Manhattan Company, which was given the exclusive right to convey water to the city.”

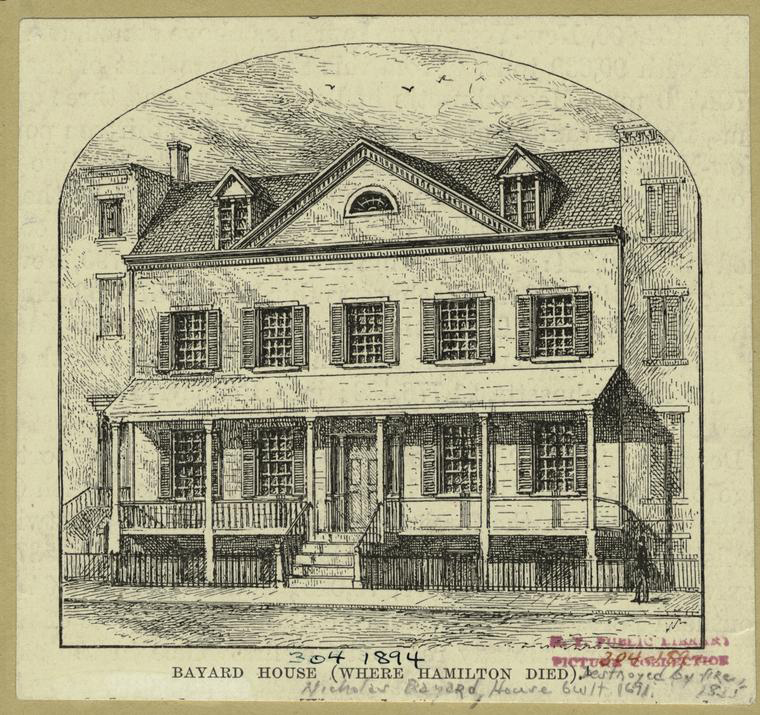

“However laudable its purpose, the act also made possible the back-door establishment of a bank, and may have contributed to the famous duel between Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton in 1804.”

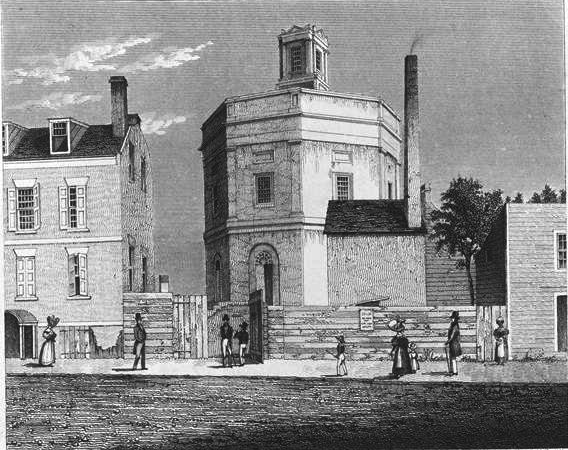

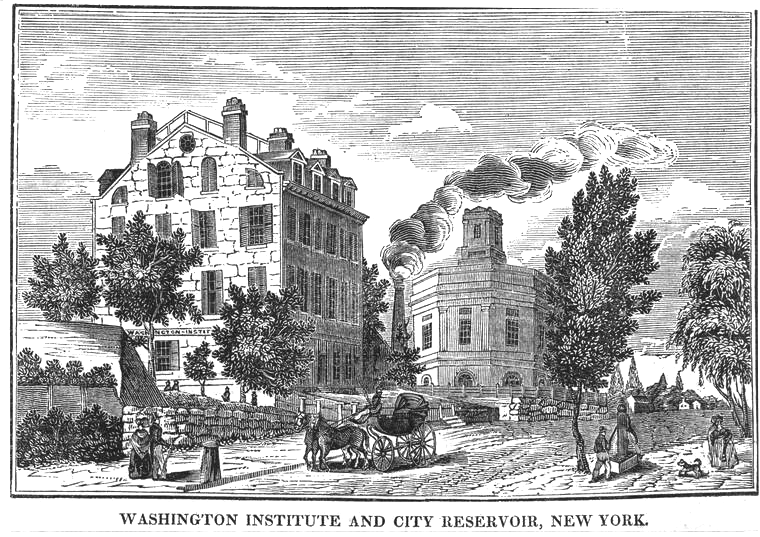

“…leading members of the Republican (now Democratic) party engaged Aaron Burr, a United States Senator, to add to the bill of incorporation for the water company a measure allowing it to use surplus capital in any transactions consistent with state law. The company thus developed a modest water system, sinking a well near the Collect, building a 550,000-gallon reservoir on Chambers Street and laying six miles of wooden mains to supply 400 families, all in its first year.”

From Liquid Assets by Diane Galusha, page 14-16.

NYC Department of Design and Construction video about the history of wooden water mains and the first piped water system in NYC: ‘A Buried History – Wooden Water Mains.’

“[The company] also wasted no time in getting into the banking business, establishing a “house of discount and deposit” at 40 Wall Street Sept. 1, 1799.”

“…the Manhattan Water Company, which had expanded its water system to include 25 miles of main and 2,000 customers, was the target of complaints from people who claimed the water it was providing was unfit for consumption and often just plain unavailable, its wooden mains clogged by roots or taken out of service for weeks at a time.”

“In 1804, continuing dissatisfaction with the water system in New York City prompted Mayor DeWitt Clinton to appoint a committee to confer with the Manhattan Company about ceding its works and water supply privilege…the company continued as a waterworks for another 35 years…”

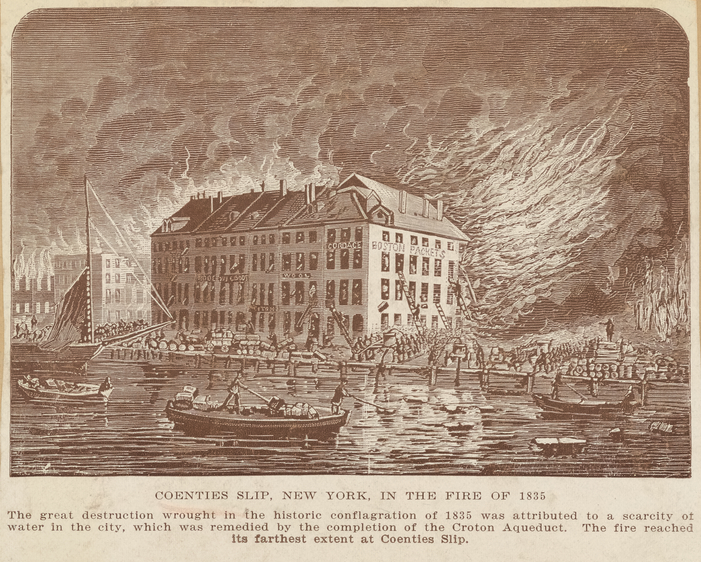

“The combination of the Manhattan Company’s small reservoir and the public and private wells that had proliferated in the polluted city continued to serve the growing metropolis in a haphazard and inadequate manner until a disastrous fire in 1828 destroyed about $600,000 in property.”

From Liquid Assets by Diane Galusha, page 14-16.

“In 1829, the council decided to build a reservoir at what was then the northernmost edge of the city, near the intersection of Bowery and 13th Street. This waterworks was not intended to provide potable water, but rather to fight fires, which became more of a threat as the city grew. The 13th Street Reservoir officially opened in April of 1831 and was drawn on successfully to put out a fire less than a month later.”

From “The Contentious History of Supplying Water to Manhattan” by Lauren Robinson in the Museum of the City of New York blog, 2013.

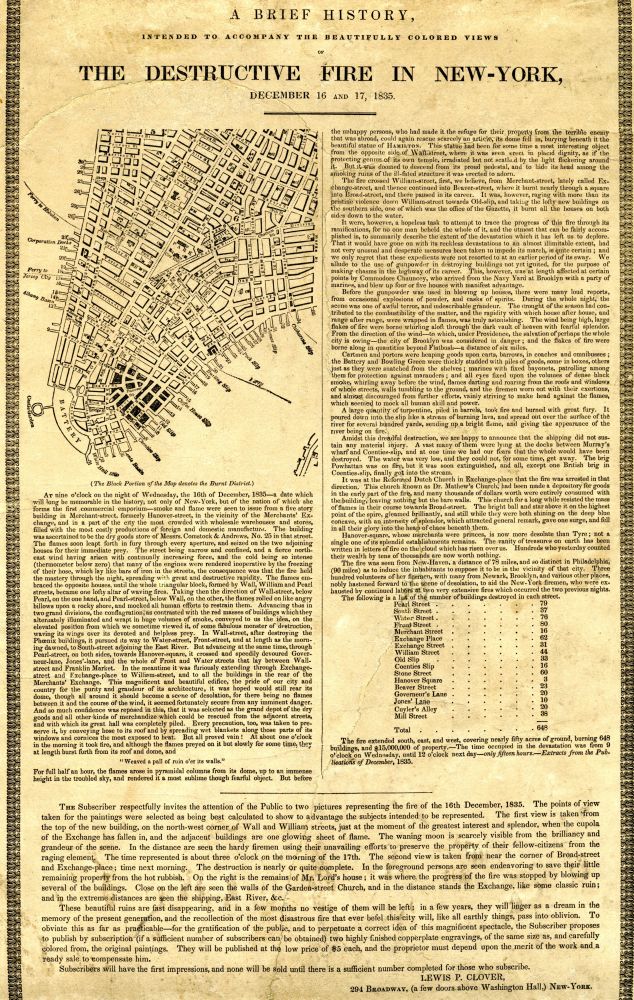

Following the fires in Manhattan in the late 1820s, the Great Fire of 1835 similarly fueled the sense of urgency in constructing effective water infrastructure and connecting the city to a sufficient water supply.

Further Reading

Liquid Assets: A History of New York City’s Water System, by Diane Galusha, Purple Mountain Press, 1999. Purchase from the Time and the Valleys Museum website.

Bottlemania: How Water Went on Sale and Why We Bought It, by Elizabeth Royte, Bloomsbury USA, 2008.

“Opinion: When New York Dabbled in Privatized Water,” by Julian Kane, Geology Professor, Hofstra U. Hempstead, L.I., May 1, 1995, New York Times.

“Dirty Water” by Maura Ferguson and Sarah Poole in the NYC Department of Records & Information Services blog, 2020.

“The Contentious History of Supplying Water to Manhattan” by Lauren Robinson in the Museum of the City of New York blog, 2013.

“The Lost 13th Street Reservoir—13th Street at 4th Avenue” by Tom Miller in Daytonian in Manhattan blog, 2013.

Privatisation of Water: A Historical Perspective by Naren Prasad for Law, Environment and Development Journal, Vol. 3/2, 2007.

Water Privatization Trends in the United States: Human Rights, National Security, and Public Stewardship by Craig Anthony (Tony) Arnold. Published in William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review Vol. 33, Issue 3, 2009.