Tanneries

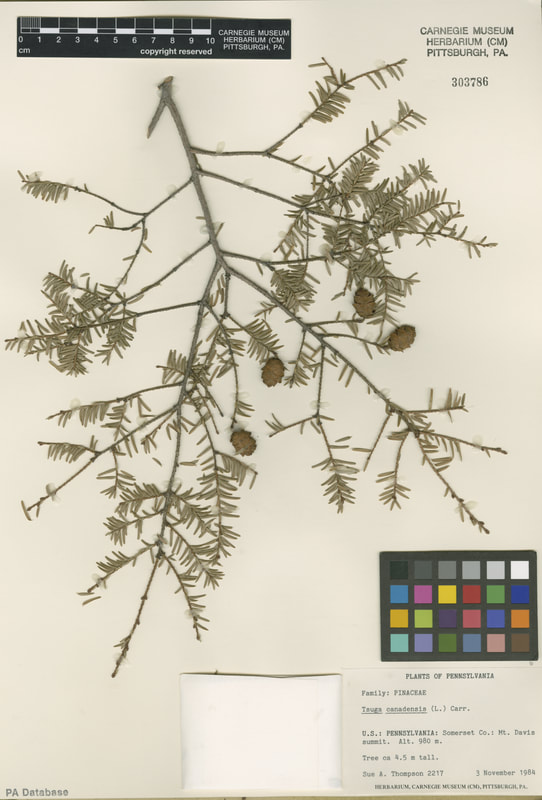

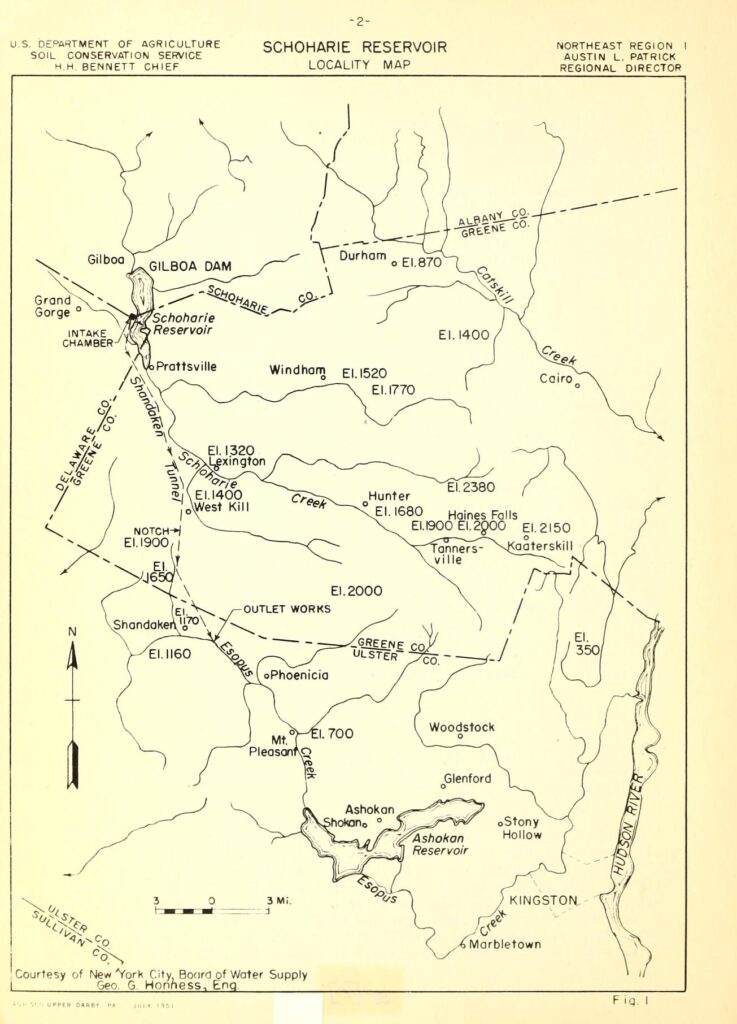

Around the same time, much of New York’s Catskill Mountain region and the Ashokan Watershed area had become central to resource extraction. Tanneries would be supplied by the area’s verdant hemlock trees, while charcoal kilns and quarries sprung up along rivers, creeks, lakes, streams and expanding trade routes.

Before the tanning industry took root in the Catskills, there was a smaller tanning business in New York. Traditionally, oak bark was used in the tanning process. Once it was discovered hemlock bark could also be used, the Catskills became an attractive region for the tanning industry.

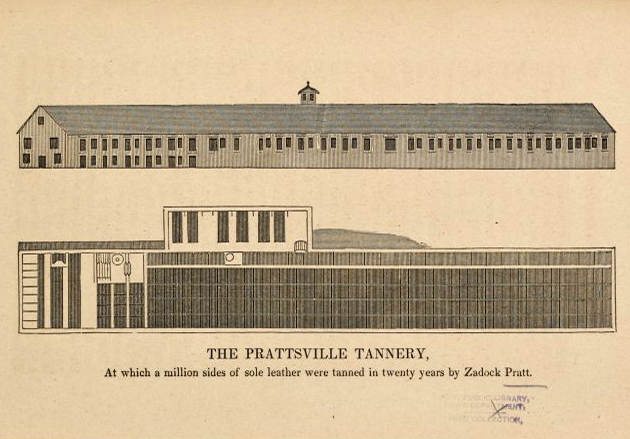

Source: Internet Archive.

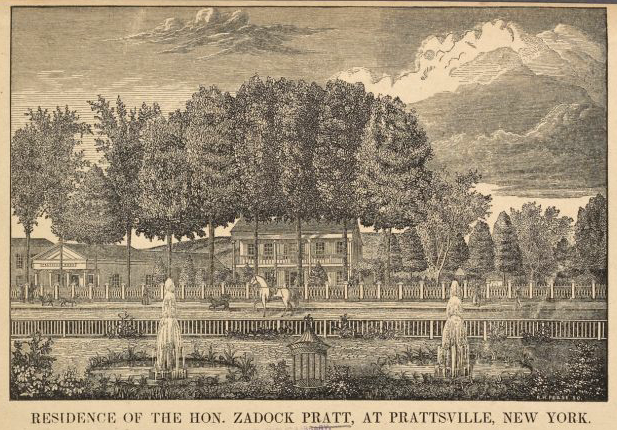

Source: NYPL Digital Collections, Division of US History, Local History and Genealogy.

“Although early Dutch settlers tanned hides from the deer they killed at the southern tip of Manhattan, New York City did not become an active leather-processing center until around 1790, when tens of thousands of hides from the West Indies and Central and South America were processed in a low, damp neighborhood just south of today’s City Hall in an area encompassing Gold, Frankfort, Pearl, Water, and Ferry Streets. Called “the Swamp,” it was so named because of tanning’s abysmal by-products–noxious odors and waste.”

From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Stephen M. SIlverman and Raphael D. Silver. (p 112)

“Three elements were essential to the tanning process: lime, to remove hair from the raw hides; an ample supply of oak bark, as a tanning agent; and enough clean water to see the hides through the tanning cycle before leaving them to dry.”

“In 1805, British chemist Sir Humphry Davy helped alter the manufacturing process with his discovery that the bark of a hemlock could be substituted for oak in providing the acid required to tan the hides… Around the Swamp, tanners were encouraged to learn that hemlock trees flourished only one hundred miles away, on the northern and western slopes of the Catskills… There were millions of these trees, which, combined with an abundance of cheap land, nearby deposits of lime, and an inexhaustible supply of pure water, made the Catskills an ideal base of operations for an industry that had long polluted New York City.”

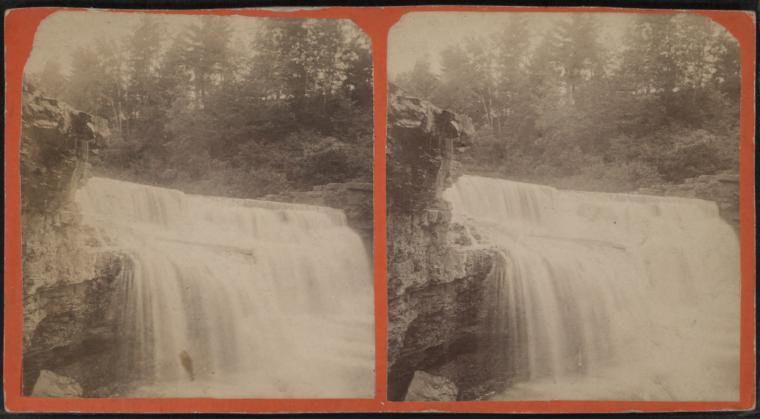

“The first tannery in the Catskills went up in 1817 near the current northern village of Palenville, close to the Hudson River.”

From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Stephen M. SIlverman and Raphael D. Silver. (p 112-113)

Source: NYPL Digital Collections, Wallach Division Print Collection.

This expansion/relocation to the Catskills in the early 19th century transformed the tanning industry. Until then, tanning businesses had been small. The industry was made up of small operations. As colonial settlement spread, new business cropped up. The Catskill tanneries were much larger than their predecessors, and they expanded production on an unprecedented scale in the young United States.

Finer leathers were still made using oak. The large quantities of leather being produced in the catskills were likely used for less visible products like the soles of shoes.

After opening in 1824, Zadock Pratt’s tannery in present day Prattsville eventually became the world’s largest of its time. A dam provided water power for Pratt’s tannery. Construction of the dam was completed in 1824.

Source: NYPL Digital Collections, Wallach Division Photography Collection. Link.

From the tanneries in the Catskills, cured leather goods were sent to New York and Boston for the final stage of production.

By locating near the banks of the Hudson, the tanneries had an easy means of transport to New York and other commercial centers. They harnessed the connective power of the river, its transportation. Before trains, planes, or cars, extractive industry outside the city was made profitable by waterways.

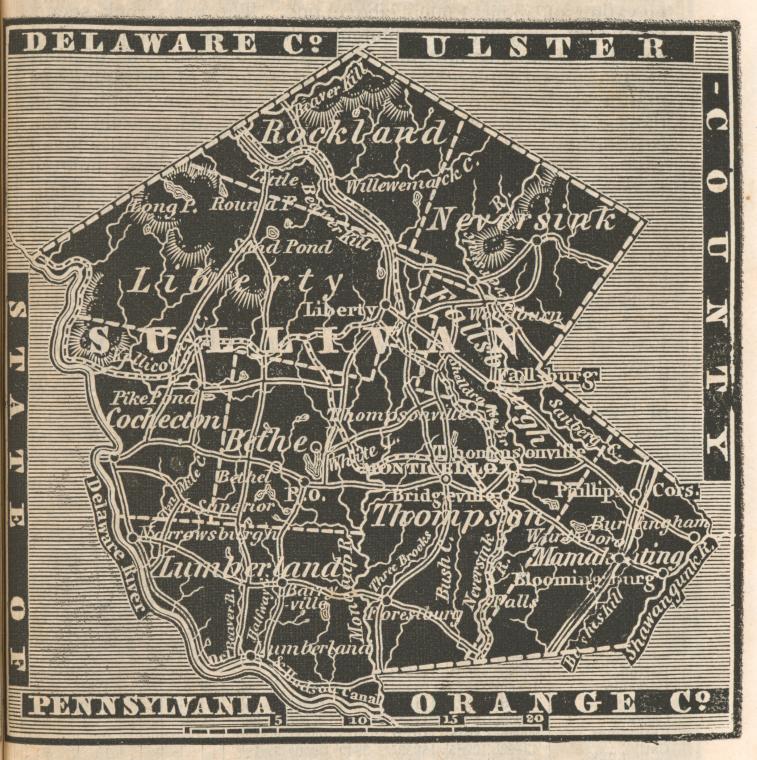

Tanning in the Catskills/Sullivan County peaked in the 1840s and started to decline in the 1900s.

“‘Sullivan County became the most prolific producer of leather, more durable and more supple and could be worked more easily than leathers from other areas,’ said [the official Sullivan County historian, John Conway].”

“For every tannery that existed, one long ton of bark, or 2,240 pounds, was required to process 250 pounds of leather. This resulted in a demand for one square mile of hemlock forest—one and a half million trees—per factory, per year.

…Trees weren’t the only fatalities. Fish vanished from streams as industrial waste raised the water temperature to dangerous levels. And once the supply of bark was exhausted in one area, tanners moved on to the next glen.

What they left behind were eyesores of rusting factories and ghost villages.”

From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver. (p 114-116)

Further Reading

“Hemlock and Hide: The Tanbark Industry in Old New York” by Hugh O. Canham in Northern Woodlands.

“Catskill Tanneries” section in Rescuing the River: 50 Years of Environmental Activism on the Hudson, online exhibit by Hudson River Valley Heritage (HRVH).

The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver.