Removing Gilboa

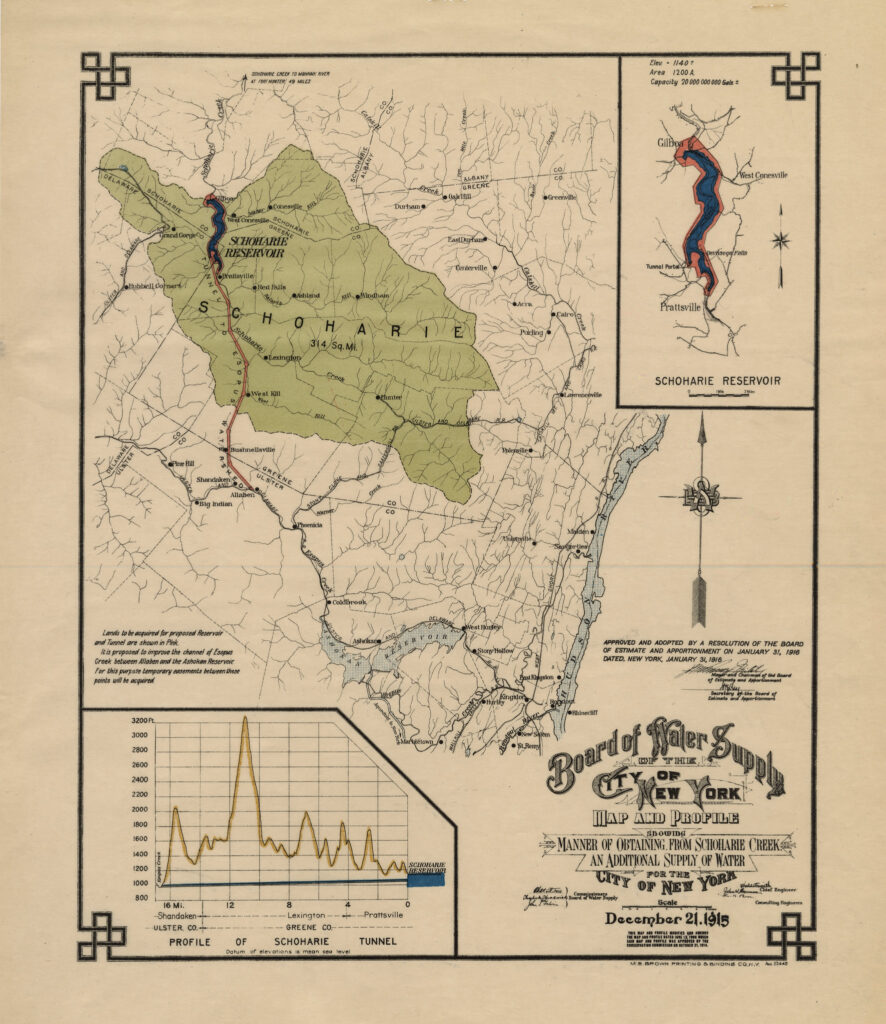

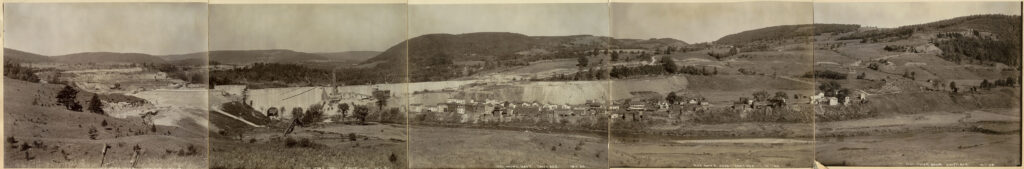

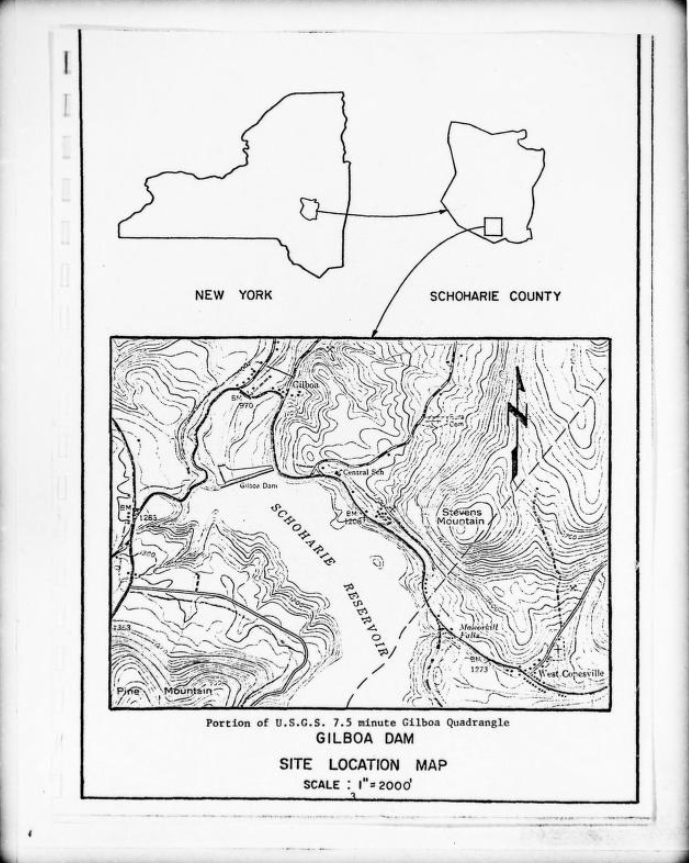

Despite the expansive Catskill system and the 130.5 billion gallon holding capacity of the Ashokan Reservoir, New York City continued to search for ways to obtain more water. In 1917, New York City acquired the village of Gilboa and a surrounding area of 2,435 acres, and the Board of Water Supply gained permission to build a dam to create the Schoharie Reservoir over the village of Gilboa (until 2020, the town of Gilboa contained the oldest known fossil forest in the world). Water from the Schoharie Reservoir would enter the Shandaken Tunnel, travel through the Esopus Creek, and eventually join the Ashokan Reservoir. The Schoharie Reservoir forced the removal of 350 residents in Gilboa and neighboring valley lands.

“Major settlement in the Town of Gilboa did not begin until the nineteenth century. In the 1840s, the Village of Gilboa began to flourish. The village developed a rural industrial economy with the establishment of cotton mills, tanneries, blacksmith shops, and other mills. Such industries were lofty attempts at increasing the local economy, but natural events, such as floods and the lack of a railroad entering the village hindered any large-scale industrial development. The flood of 1869 destroyed the Gilboa Cotton Mill Company and much of the local infrastructure. The result was the loss of the local cotton industry and a refocusing of the economy on agricultural industries.”

— From Northern Catskills History: Bringing Communities Together with a Common Heritage. Link.

“Village life ended in the early twentieth century. While major non-agricultural industry bypassed Gilboa, New York City had become one of the world’s centers of industry. Calls for increased sanitation and water sources strained the city’s local resources and prompted plans for Catskill dams and reservoirs. By tapping water sources in the Catskills, New York City could increase its access to clean water. For those remaining in the Village of Gilboa, the city’s offer to buy their property became an opportunity for a better life outside the village. With the village purchased and abandoned, New York City’s Water Bureau began construction of the Gilboa dam in 1917 and finished in 1927. The dam’s resulting reservoir submerged most of the village and over the years, trees and brush reclaimed the area around the dam. Gilboa’s farms, roads, and building foundations became overgrown, hiding the village’s historic past. Those who lived in the village have long since passed, and much of the memory of life in the village during the 1800s has faded away. However, the village’s unwritten history awaits rediscovery, and that process has begun.”

— From Northern Catskills History: Bringing Communities Together with a Common Heritage. Link.

Fossil Forests of Gilboa

Gilboa contains one of the oldest known fossil forests in the world.

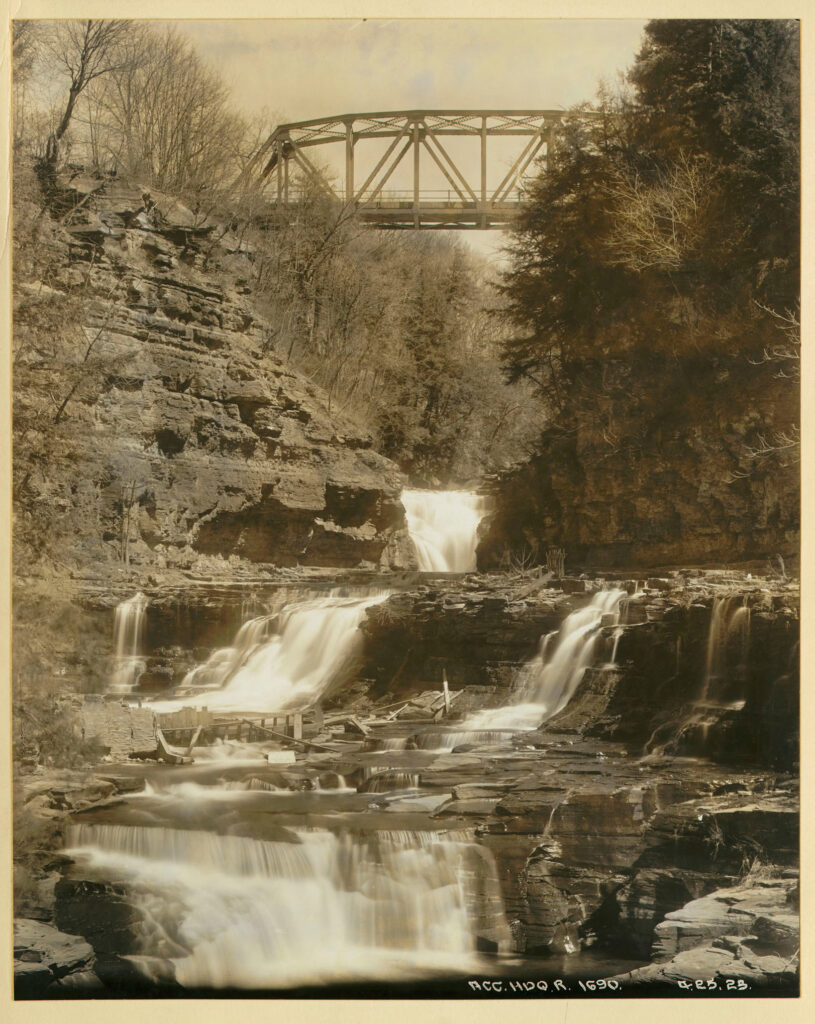

“In 1869 a large flood, termed a ‘freshet’ scoured the river banks and exposed rocks, leading to the discovery of the first fossils…To provide raw materials for the dam, the rocks along the riverbank were quarried. This uncovered many more fossils.”- From palaeocast.com, a palaeontology podcast that interviewed Professor William Stein of Bingampton University who has published research on Gilboa’s forests. Palaeocast also references information provided by the New York State Museum in Albany, NY. Link.

Over time, as many more fossils were uncovered, researchers have gained a better understanding of the kinds of trees that populate the region and been able to map out the forrest that once occupied Gilboa. When it still stood, the Gilboa’s forest was similar to the present-day palm forests located in warmer regions like Central America.

“The Gilboa trees, called Eospermatopteris, date back to the Devonian Period (roughly 380 – 385 million years ago). Eospermatopteris was one of the first plants on Earth to have a tree-like form. It resembled a fern – there was no wood on the tree – and grew to be about 30 feet tall.”- From “Re-examining the Earth’s Oldest Trees,” a New York State Museum article on paleobiology. Link.