Toxic Water, Part I

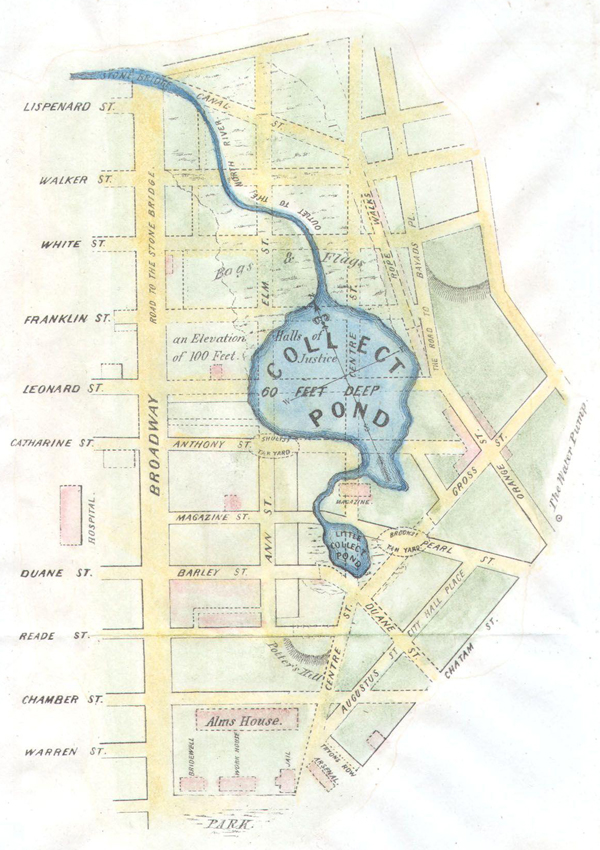

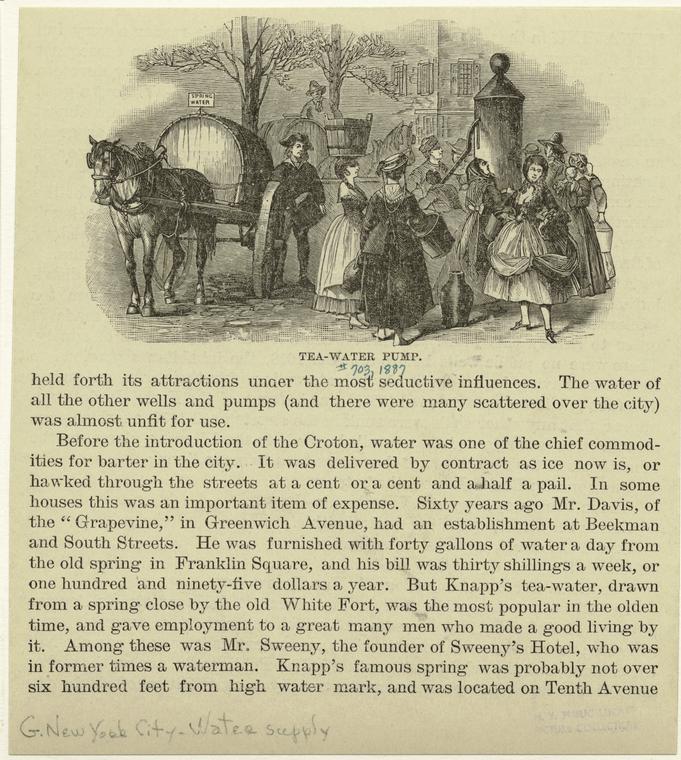

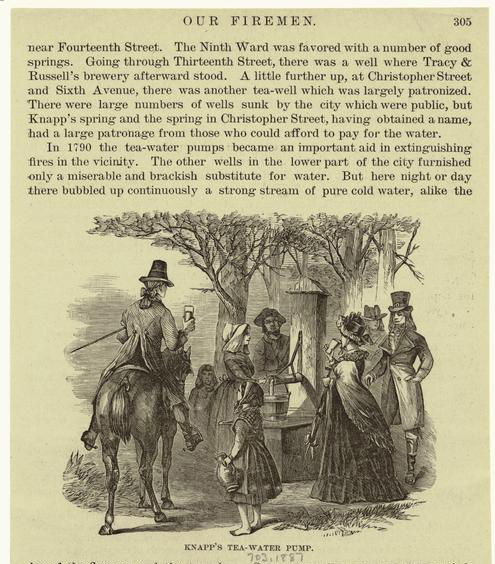

While New York City’s water is now touted as some of the cleanest, unfiltered water, this was hardly the case in the 1600’s. The first well dug in 1667 pumped briny water, so most people drank from the Collect, which was the region’s main freshwater source. However, the Collect eventually became a site to dump chamber pots, dead animals, and tannery waste. It became so polluted the city paved over it, becoming Paradise Square, then Five Points, now Collect Pond Park. In the early 1700’s cleaner water was arduously transported from Brooklyn to Manhattan, which was tapped from wells in Brooklyn and western Long Island. While Brooklyn had an adequate supply of clean groundwater, it could not meet the needs of both Brooklyn and Manhattan residents. As the city’s population increased through the 19th century, more wells were dug without separate systems for sewage and garbage. Additionally, the wells that were dug to tap groundwater were stone-lined and became contaminated with salt water from the Hudson and East Rivers.

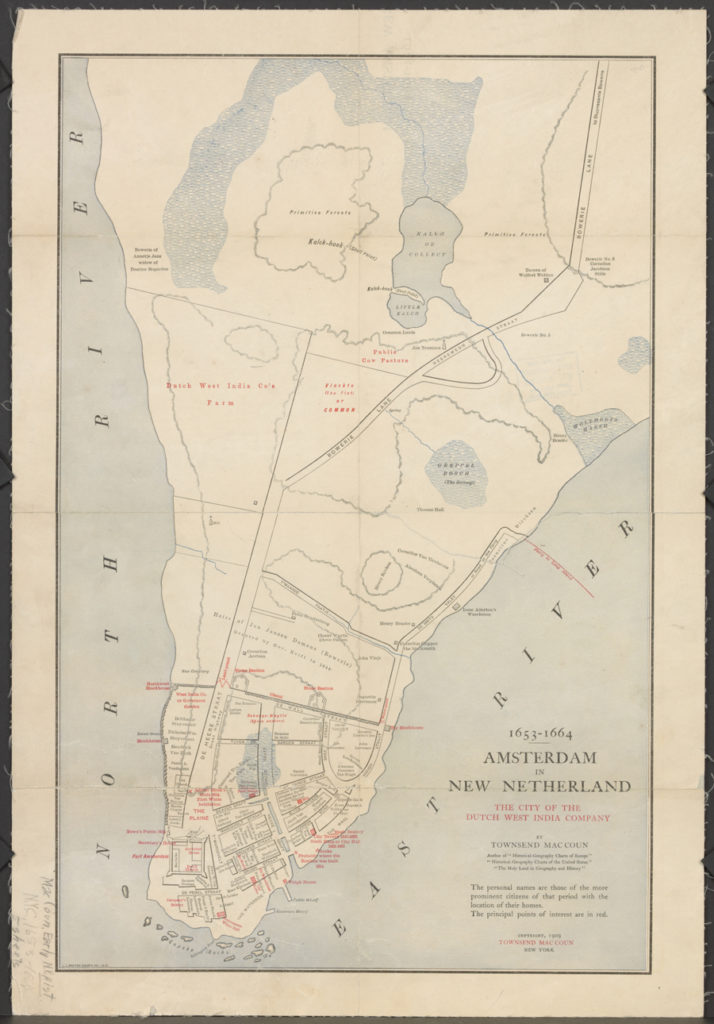

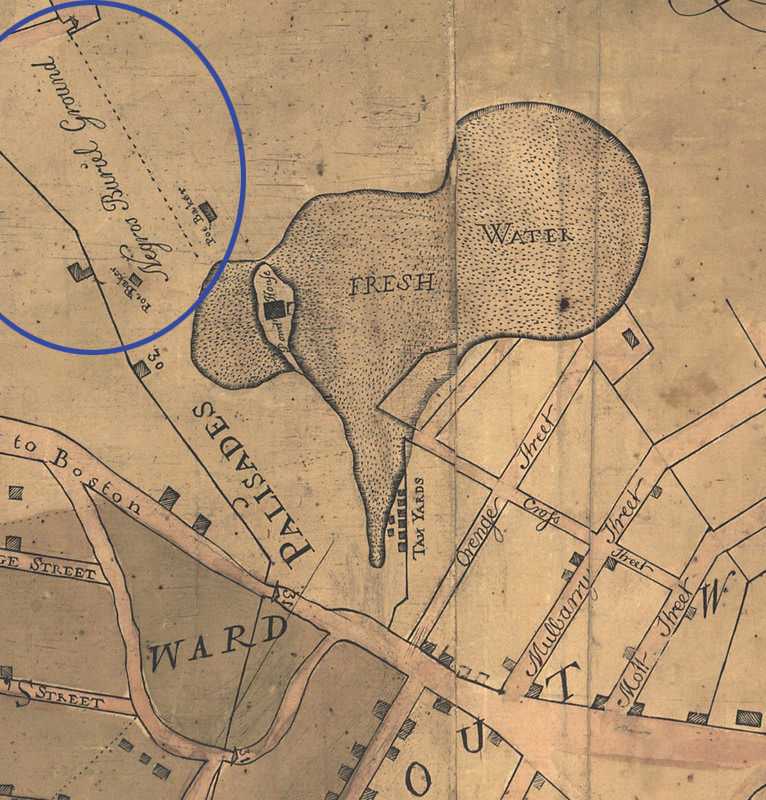

The Dutch settlement had constructed a wall around the battery believing it would secure their safety. In actuality, it contained the settlers to a swampy tip of the island with seawater seeping in. No population could be sustained without fresh water. While settlers had already begun to seize land beyond the settlement wall, the need for water further institutionalized colonial expansion on the island. To the north was Collect Pond, which quickly became New York’s main water source.

Source: Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Sergey Kadinsky on Collect Pond and surrounds in Hidden Waters of New York City:

“48 acres in an outline that includes present-day Foley Square, New York City Criminal Court, New York City Department of Health, and the New York City Supreme Court…Following the pond’s burial in 1825, its site continued to contribute to New York City’s history as the location of the notorious Five Points slum district and the Tombs prison.” (pg. 1-2)

“Christopher Colles first proposed turning Collect Pond into a reservoir in 1774. His plan involved using wooden pipes to bring water to the city.” (pg. 5)

“To the east of the pond, at the present-day intersection of Baxter and Mulberry Streets, the Tea Water Pump supplied water used for brewing tea. The pump was popular enough to be used as a reference marker on 18th-century maps, and carts delivered the pump’s water in barrels to eager customers.” (pg. 5)

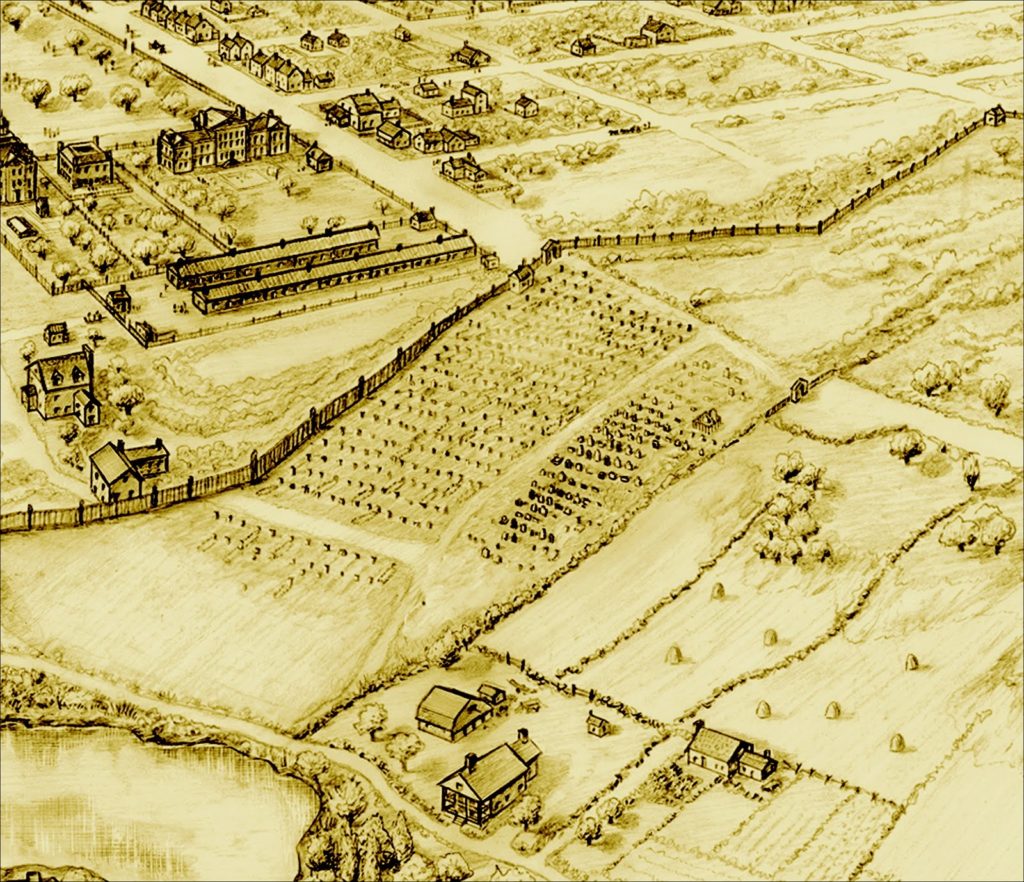

Throughout the Colonial Period both free and enslaved Black people lived in New York City. During British colonial rule Black residents were barred from owning land and burial within the city. From 1697 to 1784 between 15,000 and 20,000 people were buried in a newly established cemetery that lay north of the city, on the edge of Collect Pond. The site was re-discovered in 1991 when intact human skeletal remains were found 30 feet below the city’s street level. In 1993 the site became a a National Historic Landmark named the African Burial Ground.

Canal Street and the Draining of the Swamp

“The swamp mentioned as being to the west of the Collect stretched away to the Hudson River. It was a miry morass, permeated with the waters of the Collect, covered with a thick growth of brush and such vegetation as is usual in wet and marshy soil. It was a patch of ground useless and dangerous alike to man and beast….”

Anthony Rutgers leased the greater part of the swamp and in 1730 he proposed to irrigate the swamp by way of digging a canal in order to make the land profitable and restore it to “good ground.”

“So he had a ditch cut from the Collect Pond to the Hudson River, drained the swamp, made it firm land… and this ditch, being widened, after a while became a canal, and so gave a name to the present Canal Street.… But the cutting of the drain did more than redeem the swamp. It caused the water to flow to the Hudson River, and so lowered the surface of the Collect Pond.

It was nearing the close of the eighteenth century when the city, creeping northward by natural stages, approached the Collect, and people wondered what was to become of their pond… The Kalch Hook was cut away, and part of it dumped into the Collect. Little by little the trees upon the shores were cut down and tossed into the water… Streets passed over where it had been, and even the canal leading from it vanished.” (From When Old New York Was Young, pg. 198-203)

“During the namesake canal’s short existence, it was lined with trees planted to shield local residents from the foul water. Although the pond and its canal were both buried by 1819, the stench lingered for decades” (Hidden Waters p. 10).

Further Reading

Hidden Waters of New York by Sergey Kadinsky, book and blog.

More on Collect Pond, Canal Street, Tea-Water Pump, and lack of early sewage infrastructure, “Early Maps of Manhattan & the Evolution of the Collect Pond,” from NYCH2o.

History of Collect Pond from Tenement Museum.

African Burial Ground National Monument: History & Culture.

When old New York Was Young, Charles Hemstreet, 1902.

“From Pond to Park: The History Of The Collect Pond Site,” Robert Pigot, The Gotham Center for New York City History, 2015.

A feature with on what lies beneath NYC streets, “7 Days: The City Below,” Village Voice 1989.

“History of NYC Streets: Paradise Square,” by Kelli Trapnell in Untapped Cities, 2013.