Waste in the Watercourse

In 1915, the city secured permission to enforce health and cleanliness standards over the Catskill residents. The resulting regulations created a buffer zone where nothing could be dumped or disposed of, and by the 1920s New York City was building waste treatment plants in the Catskill villages to protect its investment in the purity of mountain water. The campaign against pollution stemmed from the hefty price tag of a filtration plant. Rather than extract more revenue from city residents to build a filtration plant, the city sought to indefinitely defer filtration by imposing its police powers on watershed residents.

“After the emergence of more modern medical and scientific perspectives on the causes of infectious water-borne diseases in the mid-1800s, policies and practices to keep sanitary waste separated from drinking water sources became a central element of public health programs, and this has been among the most important advances in human history for reducing rates of illness and mortality. But even before the real causes of these health risks were understood to be microbial pathogens, laws and policies for managing human and animal wastes to prevent contamination of drinking water sources were enacted in some parts of the U.S. Legislation was passed to protect water supplies in Philadelphia and Baltimore, in 1803 and 1808, respectively.”

“New York State’s law authorizing watershed rules and regulations was adopted in 1885, with additional provisions approved in 1909. This state law allows the NYSDOH (formed in 1900 to succeed the ‘Board of Health’) to promulgate regulations to protect specific public water supplies and their sources from contamination. To implement rules for any given water supply, the NYSDOH must enact separate regulations for that particular water system and its sources.”

— Text from a 2015 document shared by the Hudson Valley Regional Council, “Watershed Rules and Regulations for Protection of Drinking Water in New York,” a report produced by a grant-funded collaboration between NY State Environmental Protection Fund, The NY Dept. of Environmental Conservation, the Hudson River Estuary Program, the Hudson River Watershed Alliance and the Hudson Valley Regional Council.

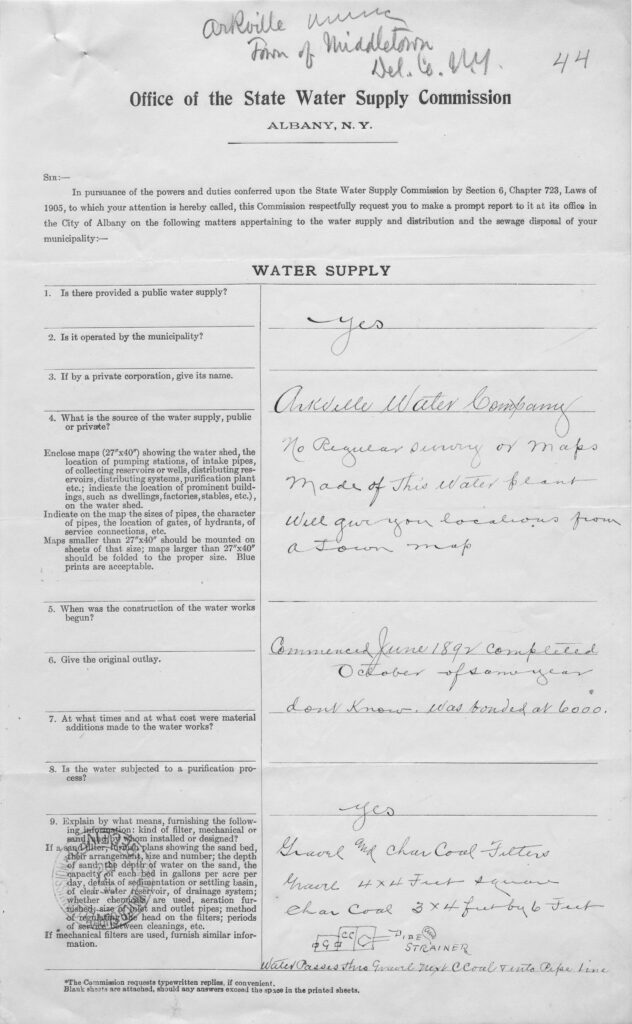

While these surveys preceded the expansion of the watershed regulation allowed by NY State law in 1909, they illustrate general trends in water management and local infrastructure in the Catskills at the start of the 20th Century.

Excerpts from the

Water Supply survey (above)

- “In pursuant of the powers and duties conferred upon the State Water Supply Commission by Section 6, Chapter 723, Laws of 1905… this Commission respectfully requests you to make a prompt report…on the following matters appertaining to the water supply and distribution and the sewage disposal of your municipality…”

- Questions include: “Is there a public water supply?” “Is it operated by the municipality?” “If by a private corporation, give its name.” “What is the source of the water supply, public or private/?” “What portion of the water shed is owned by the municipality or corporation?”

“Based on what was known in the early 1900s, these regulations generally addressed pollution sources such as privies, cesspools, garbage, animal manure, dead animals, and industrial discharges. They also often addressed fishing, boating, ice cutting, and camping. The early regulations did not address a wide range of risks to water quality that are better understood today as significant for protecting drinking water, such as sediment, fertilizer, pesticides, road salt, oil and grease, pharmaceuticals etc., some of which didn’t even exist or were not widely-used at the time.”

—From “Watershed Rules and Regulations for Protection of Drinking Water in New York,” referenced above.

Though numerous communities were disrupted or destroyed during the Catskill waterworks construction, the surrounding region and its many towns continued to make up a largely pastoral landscape with agrarian communities. Farming operations were small and produced far less waste than the massive, corporate agricultural operations that populate the U.S. today. Waste management was a consideration in limiting contamination of waterways and maintaining potable water.

As NYC was awarded greater regulatory authority over the regions supplying its drinking water, residents and communities whose land fell within the boundaries of the smaller watersheds and tributaries connected to newly constructed reservoirs, like the Ashokan and Schoharie, were subject to increasingly strict land use regulations. The City hoped to use strict regulation to avoid filtering the water supply. This would continue to be a point of contention and upstate frustration with NYC governance throughout the 20th Century.

“Over time, watershed rules and regulations were adopted by the NYSDOH for additional water supplies and generally the regulations adopted up through about 1972 included provisions similar to the earliest ones. There are at least 250 individual water supply systems for which the NYSDOH has promulgated regulations since the state law was enacted in 1885, and most regulations were adopted in the 1920s to the 1950s.”

—From “Watershed Rules and Regulations for Protection of Drinking Water in New York,” referenced above.