Water Labor

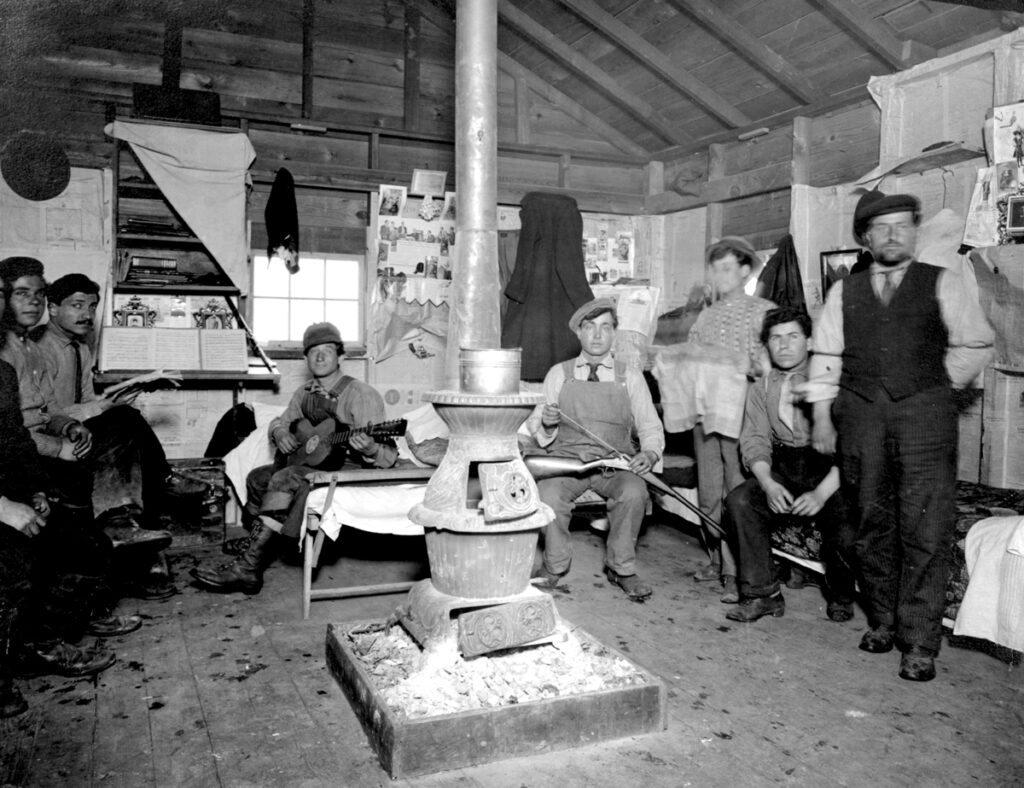

New immigrants made up the majority of the water infrastructure workforce, and they lived in camps, some with as many as 2,500 people. In keeping with the prejudices of the time, “Italian and black workers generally [occupied] separate quarters below the dam while white Americans lived separately.” –Board of Water Supply, Catskill Water Supply. Corralling workers’ waste before it contaminated local streams was one of the major unseen tasks of the waterworks project, and it employed hundreds more people. Eventually, though, waste in the camps became more controllable than waste from the Catskills neighbors, and project managers began to see Catskill residents as the biggest threat to the cleanliness of the drinking water supply.

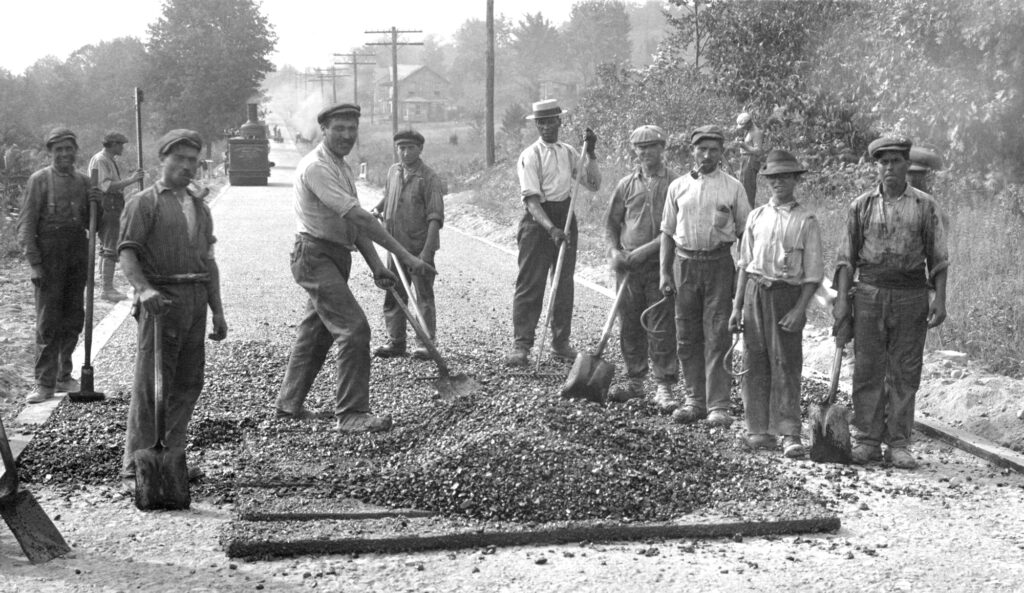

Thousands of workers built NYC’s public waterworks. This workforce, constituted in large part by recent immigrants from Ireland, Italy, and Eastern Europe and African-Americans, many of whom moved north during the Great Migration. The story of the waterworks and the people who built it has moments of solidarity and division. Immigrant and black workers faced prejudice and anger from local communities with residents largely descended from English and Dutch settlers.

Companies contracted to construct the reservoirs, dams, and aqueducts were responsible for housing their workforce. Often, they enforced discriminatory, segregationist policies, separating “Americans” from black and immigrant workers.

“Construction began in 1907 and the workforce had its own city, including a hospital, fire department, police force, sewage system, mess hall, and retail stores. Thousands of immigrants, more than half of them non-English-speaking Italian stonecutters and masons brought directly to the work site from the steamship docks in New York, were hired, as were African Americans.”

—From The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America by Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver

Yet, from the years constructing the first Croton system through the building of the Catskill waterworks, workers organized to demand fair pay and better working conditions. In the early years of the Croton construction they lacked a labor movement to support their strikes, which proved difficult to sustain. Later some of their efforts prevailed, as in 1913 when they negotiated a pay raise to $2 a day.

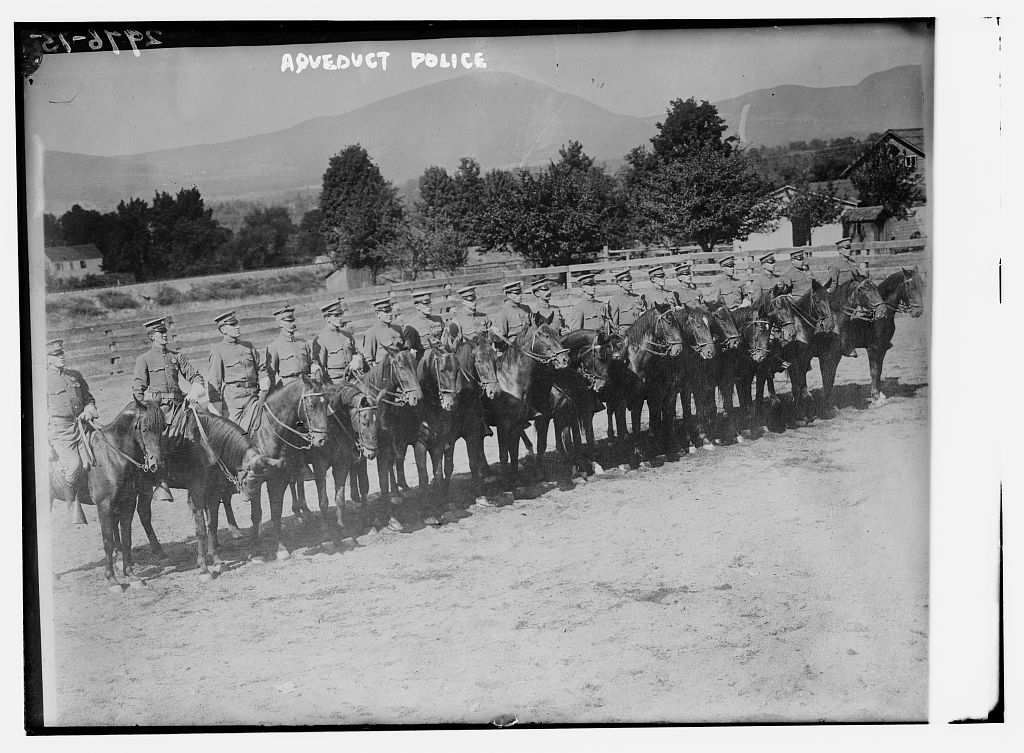

Labor actions did not go unnoticed by authorities. In 1900, soldiers were sent in to end a strike that turned violent. During the construction of the Ashokan Reservoir and Catskill Aqueduct, the Board of Water Supply employed its own mounted and armed police force to enforce order.

“The work was grueling and, all too frequently, dangerous. A local newspaper estimated that nearly 1/10th of the workers were killed or injured each year during the construction of Catskill Aqueduct: “More than 3,800 accidents, serious and otherwise, to workers on the great aqueduct have been recorded… The men doing the rough work are virtually all foreigners or negroes. Owing to the laborers being so inconspicuous, the death by accident of one or more of them attracts no public attention.”

— From Liquid Assets by Diane Galusha

To make way for the Ashokan Reservoir, laborers cleared the land of all vegetation. To build the aqueduct they moved muck, crushed stone, and blasted through earth with dynamite.

“The Ashokan Reservoir was considered the last of the ‘handmade’ dams. When you think about ‘handmade,’ for one, it was built largely by the brute force of men. And mules, lots of mules. And dynamite. It was before the era of diesel-powered heavy equipment and all the rest of the sort of labor-saving construction techniques that we know today.”

— Journalist Diane Galusha quoted in The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America

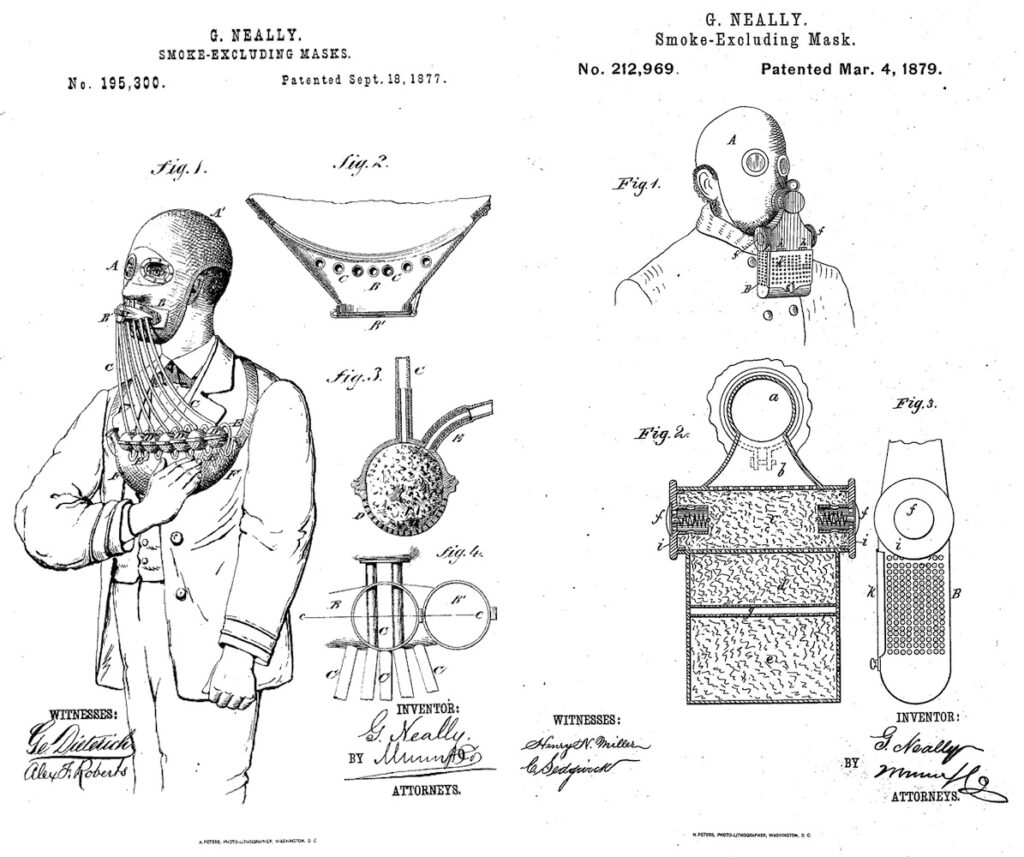

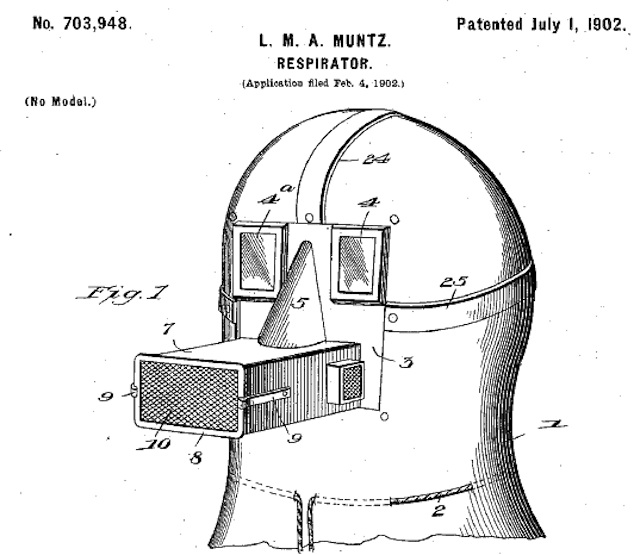

(Above) Here, the land that now forms Workers building shafts and digging tunnels were constantly breathing in dust and dirt. Working just a few years before the technological advances in respirators and gas masks brought on by the use of chemical warfare in WWI, some laborers protected themselves with the “Automated Respirator and Smoke Protector.” Journalist Diane Galusha describes this in Liquid Assets as “a mask that covered the nose and housed a wet sponge to collect inhaled dirt and dust. The sponge had to be removed and rinsed out every three hours.”

Two masks in use at the time employed sponges. First, the Smoke-Excluding Mask first patented by George Neally in 1877 and updated in 1879, “allow[ed] allow people to survive inside a smoke-filled environment such as a burning building. The mask includes moist sponges that filter out smoke particles.” The second, the Muntz Respirator, patented in 1902, was “a full head-covering mask with a sponge- and a carbon-based filter.”